Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Program Evaluation

4. Evaluation Findings

4.1. Relevance

The evaluation considered the relevance of the CAHWC Program with respect to: the continued need for the Program; the responsiveness of the Program to federal government priorities, roles, and responsibilities; and the Program’s support for each partner’s strategic outcomes.

4.1.1. Continued need for the CAHWC Program

The evaluation confirmed there is an ongoing need for the Program for the following reasons:

Canada has ongoing international and domestic legal obligations to end impunity

The Program remains relevant because Canada is party to United Nations (UN) conventions on genocide, refugees, torture, war crimes, and, most recently, the Rome Statute (each of these legal obligations is discussed further in Section 4.1.4 below), and Canada has domestic responsibilities under the CAHWC Act, IRPA and the Citizenship Act. Therefore, these obligations require Canada to provide safe haven to refugees fleeing areas of prolonged conflict, but also require Canada to be vigilant in ensuring persons who committed or were complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide are not allowed to enter or remain in Canada and, when appropriate, are prosecuted for their crimes.

Atrocities continue to be committed

Many key informants explained that crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide continue to be committed as part of modern, non-conventional warfare, referring to conflicts and upheaval in countries such as Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, South Sudan, or more specifically to extremist groups such as ISIS/ISIL and Boko Haram. Over the past several years, the UN has released numerous reports on the growing potential for, or observed commission of, war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Central African Republic, Sudan, South Sudan, Iraq, and SyriaFootnote 17. Specific concerns relate to recruitment of children and forced deportations in the Central African Republic (UNNC, 2011a), indiscriminate attacks on civilians and extrajudicial killings in Sudan (UNNC, 2011b, 2011c), warnings over the precursors to genocide, extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and the use of children in armed conflicts in South Sudan (UNNC, 2014b, 2015b), and ISIS/ISIL’s use of torture, rape, starvation, abduction and conscription of children, sexual slavery, mass executions, and targeted violence against the Yezidi minority in Iraq and Syria (UNNC, 2014a, 2015a, 2016a, 2016b). Most recently, the UN has reported there were at least 18,802 Iraqi civilian deaths and 36,245 civilians injured between January 2014 and October 2015 as a result of the continuing conflict in Iraq; while many of the killings are attributed to ISIL, government security forces, militias, tribal forces, and Kurdish Peshmerga are also implicated in the widespread violence (UNNC, 2016a).

Canada is an immigrant- and refugee-receiving country and is therefore a potential destination for witnesses, victims, and perpetrators of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide

The Program remains relevant because it provides interdepartmental coordination and expertise to ensure there are resources available to follow up on crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide allegations against individuals thought to be in Canada. Evidence from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) shows many of the high-conflict countries discussed above are among the top refugee-producing countries in the worldFootnote 18 and Canada is among the countries receiving immigrants and refugees from these areas. For example, Program data and documentary sources show that between 2008 and 2014, Iraq was the 10th largest source country for immigrants and refugees to Canada. Data from the UNHCR shows Canada has received several thousand refugees from other major conflict areas including Afghanistan and Somalia, as well as Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan (CBSA et al., 2011, p. 19; UNHCR, n.d). Most recently, the Government of Canada resettled 25,000 Syrian refugees by the end of February 2016 (GoC, 2016).

The Program also remains relevant as a coordinating point through which IRCC and the CBSA screen for inadmissibility under subsection 35(1) of IRPA. One aspect of security screening is to identify perpetrators of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide and prevent them from attempting to seek refuge in Canada. As of 2011, there were nine regimes designated under paragraph 35(1)(b) of IRPA for crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide (among other international crimes) (CBSA et al., 2011, p. 19). There have been no new regimes designated since 2003, which is when paragraph 35(1)(c) of IRPA was added. According to visa data over an eight-year period, over one-tenth of visa applicants who were screened for crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide were denied entry to Canada. From 2003–2004 to 2013–2014, this amounted to about 2,800 visa applications denied for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

Domestic efforts to address crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide are of increasing importance

Although international courts and tribunals demonstrate a commitment to addressing modern war crimes, national efforts — such as Canada’s CAHWC Program — are neither redundant nor unnecessary. Firstly, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia is winding down, while the one for Rwanda is already closed. Several Program and NGO/academic key informants noted how the shift toward domestic prosecutions will put greater pressure on domestic resources for costly investigations and prosecutions and will create a greater need for domestic expertise on issues related to crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. This may be particularly challenging for countries that are less developed and/or have only just begun to rebuild their legal and police infrastructures following prolonged periods of conflict. Secondly, some Program and NGO/academic key informants noted that as the court of last resort, the ICC’s jurisdiction is limited to those conflicts where individual states cannot or will not investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. A few of these key informants noted this put greater pressure on nations to pursue domestic investigations and prosecutions.

4.1.2. Does the Program meet government policy priorities?

The Program enforces Canada’s no safe haven policy and has fitted within the Government of Canada’s policy agenda

Evidence from key informant opinions and federal government statements (e.g., Speeches from the Throne and budget speeches) demonstrate that the Program has continued to meet government policy priorities. Key informants from partner departments/agencies believed the Program meets the policy priorities of the government, indicating the Program enforces Canada’s no safe haven policy and has fit comfortably within the Government of Canada’s law and order agenda.

Speeches from the Throne and federal budgets identified a number of priority areas that specifically relate to crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. For example, the 2009 Speech from the Throne emphasized the need to strengthen border security, maintain the integrity of the immigration regime, and reform the refugee system, all of which are interlinked with the objectives of the CAHWC Program. During the 2010 Speech from the Throne, the federal government announced its intention to introduce legislation to speed up the citizenship revocation process for those who have concealed their participation in crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. These changes were announced through Bill C-24 and became law through the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act, which came into effect in May 2015 (CIC, 2015). The new laws are anticipated to improve the efficiency of citizenship revocations, which have traditionally taken several years to complete, and have thus affected Program performance. Finally, in 2011 the federal government committed $8.4 million per year in permanent funding toward Canada’s no safe havenpolicy. This was in addition to the $7.2 million in permanent funding the CBSA already received for its CAHWC Program activities. While not an increase in funding, the move to permanent funding demonstrated an alignment between the Program and government priority objectives.

4.1.3. Does the Program align with departmental strategic outcomes and priorities?

The CAHWC Program aligns with departmental strategic outcomes and priorities

The evaluation found that generally, the Program aligns with departmental strategic outcomes. While the Program is usually not specifically mentioned among its partners’ strategic outcomes, the essence of the Program is indirectly supported through several strategic outcomes, as summarized in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Alignment of the Program with departmental strategic outcomes

Justice

- A fair, relevant, and accessible Canadian justice system

- This strategic outcome includes the development and provision of services related to criminal law and policy. The CAHWC Program aligns with this outcome through the Justice policy work that relates to the legislative framework for pursuing individuals suspected of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

- A federal government that is supported by high-quality legal services

- The CAHWC Section of Justice supports this strategic outcome by providing legal advice and support to the RCMP in conducting investigations and providing legal advice related to Program activities undertaken by the CBSA and IRCC. In addition, the CAHWC Section supports criminal prosecutions of those suspected of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

RCMP

- Criminal activity affecting Canadians is reduced

- Under the federal policing sub-program, the RCMP “enforces federal laws and protects Canada's institutions, national security, and Canadian and foreign dignitaries.” (RCMP, 2015). The CAHWC Program aligns with this strategic outcome and sub-program through its federal crime enforcement activities, namely, its work conducting criminal investigations related to those individuals suspected of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. The RCMP’s war crimes work is explicitly identified as falling under this strategic outcome (specifically, the Federal Crime Enforcement sub-sub-program (1.1.2.4), which contributes to increasing public confidence in the integrity of federal programs and services).

CBSA

- International trade and travel is facilitated across Canada’s border and Canada’s population is protected from border-related risks

- The CAHWC Program aligns with this CBSA strategic outcome as it operates to screen and flag individuals believed to have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide, and when appropriate, enforce orders to remove these individuals from Canada. In so doing, the integrity of the immigration system is upheld by not providing safe haven to individuals believed to have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes or genocide.

IRCC

- Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society

- This outcome includes the revocation of citizenship when a person has obtained it fraudulently by knowingly misrepresenting or concealing information, such as involvement in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

- Managed migration that promotes Canadian interests and protects the health, safety, and security of Canadians

- This strategic outcome incorporates IRCC’s Migration Control and Security Management Program area, which “aims to ensure the managed migration of foreign nationals and newcomers to Canada” (CIC, 2014b). This is done by ensuring that migration is in accordance with IRPA and accompanying regulations, which is done through the institution of anti-fraud measures and eligibility and admissibility criteria, some of which operate to keep individuals suspected of committing or being complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide out of Canada.

Sources: (CBSA, 2015; CIC, 2014a; Department of Justice Canada, 2015a; RCMP, 2015)

In addition, general Government of Canada priorities to invest in crime prevention and the justice system (2011 Federal Budget), combat crime and terrorism (2011 Speech from the Throne), and uphold victims’ rights (2013 Speech from the Throne) can be more broadly interpreted as being compatible with the goals of the CAHWC Program

Key informants from all partner departments/agencies also believe that the CAHWC Program aligns with their department’s/agency’s strategic outcomes and priorities. For example, the CBSA is responsible for providing integrated border security that supports national security and public safety priorities, and facilitates the free flow of persons and goods. Immigration enforcement to keep individuals who are inadmissible for crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide from entering Canada is seen as a continuing priority at the CBSA in relation to the CAHWC Program. Three of IRCC’s operational objectives — preventing admission, detecting involvement, and revoking citizenship — are relevant to the Program and underlie its strategic outcomes. Both Justice and RCMP key informants also believe that the CAHWC Program remains relevant to departmental priorities.

4.1.4. Is there still a role for the federal government to deliver the Program?

The Canadian legislative framework obligates the federal government to continue to act to prevent and deter entry, or remove individuals who have committed or are complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide

The Government of Canada has exercised its authority to create a legislative framework that obligates the federal government to continue to act to prevent and deter entry, or remove individuals who have committed or are complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. The government has remedies available in the following legislation: the CAHWC Act, the Extradition Act, IRPA, the Citizenship Act, and the Criminal Code. Furthermore, as shown in Table 5, the Government of Canada has signed a number of international agreements that, among other things, obligate Canada to provide safe haven to refugees while ensuring perpetrators of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide are excluded, removed, or prosecuted.

Table 5: International commitments and obligations related to addressing crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1949)

- Declares genocide as a crime under international law and specifies actions that constitute genocide.

- Convention on the Status of Refugees (1951)

- Defines a Convention refugee, including refugee rights and criteria for exclusion from refugee protection, which includes commission of a crime against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity or a serious non-political crime outside their country of refuge. Canada is also signatory to the 1967 Protocol, which expanded the applicability of the 1951 Convention, removing geographical and time limits that restricted the definition of refugee.

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1987):

- Builds upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international covenants by further defining the act of torture and obligation of the state.

- Geneva Conventions of 1949 and additional protocols

- Provides rules limiting the effects of conflict in an effort to protect civilians and others who are not taking part in the conflict (civilians, aid workers) and those who can no longer fight (wounded, prisoners of war) (ICRC, 2010).

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (2002)

- Defines the rules, mechanisms, and jurisdiction of the ICC and established the principle of complementarity, where states have the primary responsibility to investigate and prosecute CAHWC and genocide domestically. Canada is among 65 other countries that have enacted legislation containing complementarity or cooperation provisions (or both) to implement the Rome Statute (ICC, n.d). The complementarity principle establishes that state parties (such as Canada) have the primary responsibility for investigating and prosecuting persons who have committed or are complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

4.2. Performance – Effectiveness

According to the 2009 Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation, evaluating performance involves assessing effectiveness, as well as efficiency and economy. The subsections below discuss the effectiveness of the CAHWC Program in achieving its expected outcomes.

4.2.1. Increasing knowledge and awareness of the Program

The Program is expected to engage in training, development of tools and policies, knowledge management, and outreach activities that, taken together, are intended to increase knowledge and awareness of the Program both internally and externally, resulting in more effective Program delivery. Before looking at each of those activities, this section considers departmental and agency staff perceptions of their knowledge of all the Program components, as well as the clarity of roles and responsibilities within the Program.

Partner staff are generally knowledgeable about the Program and consider roles to be clear

The evaluation findings indicate that department and agency staff who undertake work related to the Program are generally knowledgeable of the Program’s components, although the level of knowledge is affected by various factors. The majority of respondents (66%) rated themselves as knowledgeable (31%) or somewhat knowledgeable (35%) of all Program components, including components outside their own areas of the Program. Factors affecting the self-assessment of knowledge are the years of experience, the department/agency of the respondent, and, to a lesser extent, the locations (overseas, region, headquarters) where the respondent worked.

- Respondents from Justice and the CBSA tended to rate themselves as knowledgeable or very knowledgeable, while respondents from IRCC and the RCMP tended to rate themselves as somewhat knowledgeable.

- Respondents with more than five years’ experience were more likely to consider themselves very knowledgeable or knowledgeable compared to those respondents with less experience.

- Based on their self-assessment, respondents who had worked at headquarters were slightly more knowledgeable than those who worked only in the regions or overseas.

| Response | Very knowledgeable | Knowledgeable | Somewhat knowledgeable | Not knowledgeable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Overall | 16 | 24% | 21 | 31% | 24 | 35% | 7 | 10% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Caution: Small sample size.

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

| Response | Very knowledgeable | Knowledgeable | Somewhat knowledgeable | Not knowledgeable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| CBSA | 7 | 32% | 7 | 32% | 6 | 27% | 2 | 9% |

| IRCC | -- | -- | 3 | 38% | 5 | 63% | -- | -- |

| Justice | 7 | 39% | 6 | 32% | 4 | 21% | 2 | 11% |

| RCMP | 2 | 11% | 5 | 26% | 9 | 47% | 3 | 16% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Caution: Small sample size.

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

| Response | Very knowledgeable | Knowledgeable | Somewhat knowledgeable | Not knowledgeable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Less than 1 year | -- | -- | -- | -- | 2 | 40% | 3 | 60% |

| 1–5 years | 2 | 8% | 9 | 35% | 12 | 46% | 3 | 12% |

| 6–10 years | 6 | 35% | 7 | 41% | 4 | 24% | -- | -- |

| Over 10 years | 8 | 40% | 5 | 25% | 6 | 30% | 1 | 5% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Caution: Small sample size.

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

| Response | Very knowledgeable | Knowledgeable | Somewhat knowledgeable | Not knowledgeable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| National HeadquartersTable note i | 9 | 27% | 14 | 41% | 9 | 27% | 2 | 6% |

| Regional unit (only) | 7 | 35% | 4 | 20% | 6 | 30% | 3 | 15% |

| Overseas mission (only) | -- | -- | 3 | 23% | 8 | 62% | 2 | 15% |

| Other | -- | -- | -- | -- | 1 | 100% | -- | -- |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Caution: Small sample size.

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

- Table note i

-

If respondents indicated they had worked at NHQ as well as another location, they are included under NHQ for the purpose of this analysis.

Key informants from partner departments and agencies confirmed and provided context for the survey findings. They reported that an understanding of the Program’s various components is much greater for senior staff. Key informants explained that awareness of the Program for staff working in regional offices or overseas may be somewhat lower than for staff working at headquarters because cases related to crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide are rare and their knowledge would be limited to operational policy related to these crimes.

Roles and responsibilities of the partner departments and agencies are generally clear, based on interview and survey findings. Survey results showed most respondents (66%) believe they understand the roles and responsibilities of each partner, although the majority only somewhat agree that the roles of other departments and agencies are clear (see Table 7).

| Response | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Agree | 10 | 15% |

| Somewhat agree | 35 | 51% |

| Somewhat disagree | 8 | 12% |

| Disagree | 8 | 12% |

| Not applicable to my work | 3 | 4% |

| Don't know | 4 | 6% |

| Total | 68 | 100% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Some key informants from the Program provided additional context, noting that changes in structure and personnel within partner departments and agencies have meant that, while each partner’s role is understood, the roles and responsibilities within partner departments and agencies are less clear to other partners. Additionally, they noted that the complexity of remedies also means that partners not directly involved in a remedy do not have the in-depth knowledge of the process. For these reasons, having greater regularity of PCOC meetings and consistent representation of all partners, including representation from the appropriate divisions within partner departments and agencies, is considered vital to the effective operations of the Program. A few key informants mentioned issues with this in the past, when lack of understanding of the different roles within a partner department or agency meant that not all of the relevant people were consulted on an issue being considered by PCOC.

Training of Program partner staff is considered to have declined in terms of availability and adequacy

Based on interview and documentary evidence, the evaluation found that training continues to occur, although complete details for all training activities were not available. Interview and survey results indicate that training is an area for improvement in terms of amount available, level of training, and subject matter of training.

The documentary record of Program training activities does not provide the full extent and type of training offered. While outreach and training activities are discussed at PCOC as a standing agenda item, the focus is more on outreach and few training activities are mentioned. While maintaining a record of these activities was discussed at PCOC, the tool for tracking training and outreach was not developed.

Key informants from partner departments and agencies noted that the availability and adequacy of training specific to crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide has declined over the last several years. Some key informants considered training to be less regular, specific and collaborative than in the past, when the Program was in its early stages. The training challenges took different forms for each partner.

- Interviewees from Justice indicate training programs for counsel are hampered by a lack of funding and challenges in accessing that funding. They pointed out that training, particularly for more experienced counsel, requires international travel as this training is quite specialized and, if training is offered within Canada, experienced or senior counsel within the CAHWC Section are often providing the training.

- Although the CBSA key informants and internal documents praise the Agency’s 2014 War Crimes Intelligence Workshop,Footnote 19 and Agency personnel are pleased with the regular one-on-one “walk through” guidance offered by Justice on specific files, there was concern about the lack of training opportunities at the regional level and the limits of regional travel budgets, which would preclude regional staff from attending Ottawa-based training. They noted that the CBSA generally uses enforcement and operational bulletins to inform personnel about operational policies and address potential gaps, rather than offer formal training.

- Key informants from IRCC noted there is a lack of training tools for regional staff, particularly on the citizenship side. Much of the relevant CAHWC-related training appears to be targeted at overseas IRCC visa officers, and includes refresher courses on the CAHWC Act and regulations and the ability to seek advice through IRCC’s Case Management Branch, which provides guidance on individual cases.

- Although Justice conducted formal training with the RCMP in the past, this has not occurred in recent years, and RCMP interviewees indicated that there is currently no specific training for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide. These key informants considered the development of standard, Program-specific training to be challenging because, while much of the essential skills for investigating these crimes are no different from homicide investigations, the contexts within these foreign jurisdictions are unique, differing from case to case. A few key informants emphasized the importance of understanding the specific cultural contexts.

Survey results aligned with key informant opinions. The majority of survey respondents (68%) reported that the amount of training provided is inadequate. These opinions were common across all respondent departments, but were most prominent among the CBSA and IRCC respondents. In addition, just over half of all respondents (53%) disagreed that the level of training available is suitable for someone with their amount of time on the job and responsibilities. These opinions were more prominent among respondents who had worked in areas related to addressing crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide for more than one year. Finally, respondents were somewhat more mixed about whether the subject matter of their current training met their needs, with some (43%) disagreeing and some (38%) agreeing. Table 8 presents overall results.

| Response | Agree | Somewhat agree | Somewhat disagree | Disagree | Not applicable to my work | Don't know | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| The subject matter of current training meets my needs | 8 | 12% | 18 | 26% | 13 | 19% | 16 | 24% | 6 | 9% | 7 | 10% |

| The level of training is suitable for someone with my time on the job and responsibilities | 8 | 12% | 14 | 21% | 19 | 28% | 17 | 25% | 7 | 10% | 3 | 4% |

| The amount of training provided is adequate | 6 | 9% | 8 | 12% | 27 | 40% | 19 | 28% | 5 | 7% | 3 | 4% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

Key informants offered some suggestions for how to improve training:

- Partners should offer more online training (e.g., webinars) and explore other delivery methods that will expand the reach of training opportunities to regional offices.

- Training should become more standardized, as training currently differs across regional offices in the CBSA.

- Some key informants wanted more training on Section 35 of IRPA.

- A few key informants commented that some departments used to offer annual sessions, and wished these could be reinstituted. Two sessions were specifically mentioned: a two-day training session or “open house” given by Justice; and an annual meeting hosted by IRCC, which was considered a valuable opportunity to learn IRCC’s perspective and make contacts.

- Justice staff in the CAHWC Section expressed the desire for opportunities to receive litigation training and experience.

- As Justice will be ‘investigating’ civil cases, the RCMP key informants suggested it may be beneficial for them to have training in interviewing techniques and obtaining witness statements.

Program tools, policies, and procedures are generally considered useful, although areas for improvement were identified

The Program partners have, over time, developed a number of tools, policies, and procedures. Most of these were initially developed outside of the time period covered by the evaluation, but may have been updated or revised since then.

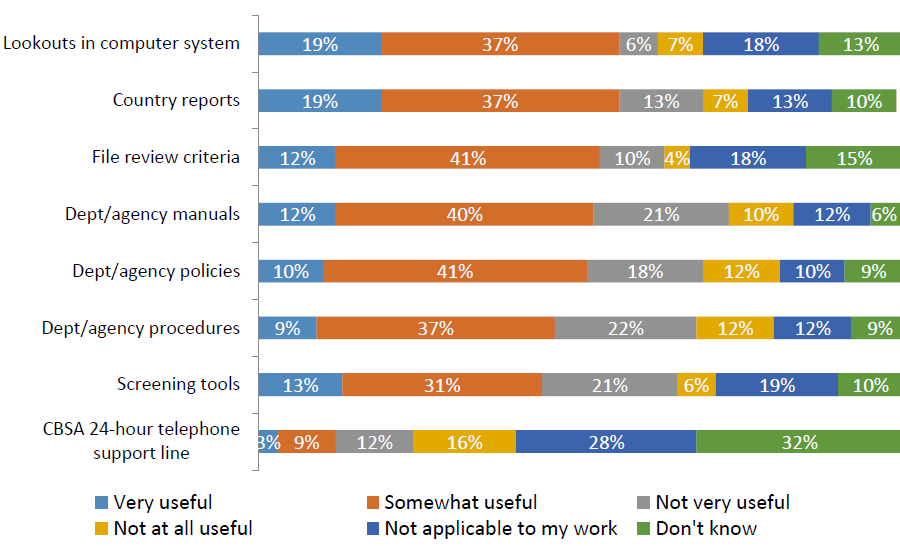

Among survey respondents who were able to comment on the various tools, policies, and procedures, most considered them to be very or somewhat useful. However, for department or agency policies, procedures, and manuals, which should be relevant to all staff, about one-fifth of respondents did not consider them applicable to their work or did not have enough experience with them to rate their usefulness. This result may indicate a need to create more awareness of these tools, policies, and procedures related to the work of the Program. The survey responses also indicate room for improving these resources. For example, about one-third of respondents considered their department or agency’s procedures (34%), manuals (31%) and policies (30%) to be not very useful or not at all useful.

Based on survey results, the tools considered least useful are the CBSA 24-hour telephone support line and screening tools, and those considered most useful are lookouts in computer systems, country reports, and the file review criteria. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Usefulness of tools, policies, and procedures

Q20: How useful are the following tools, policies, and procedures to your work related to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide?

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Figure 1: Usefulness of tools, policies, and procedures - Text Version

Q20: How useful are the following tools, policies, and procedures to your work related to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide?

Lookouts in computer system were found to be very useful by 19% of survey respondents, somewhat useful by 37%, not very useful by 6%, not at all useful by 7%, not applicable to my work by 18% and 13% indicated they did not know.

Country reports were found to be very useful by 19%, somewhat useful by 37%, not very useful by 13%, not at all useful by 7%, not applicable to my work by 13% and 10% did not know.

File review criteria were found to be very useful by 12%, somewhat useful by 41%, not very useful by 10%, not at all useful by 4%, not applicable to my work by 18% and 15% did not know.

Department or agency manuals were found to be very useful by 12%, somewhat useful by 40%, not very useful by 21%, not at all useful by 10%, not applicable to my work by 12% and 6% did not know.

Department or agency policies were found to be very useful by 10%, somewhat useful by 41%, not very useful by 18%, not at all useful by 12%, not applicable to my work by 10% and 9% did not know.

Department or agency procedures were found to be very useful by 9%, somewhat useful by 37%, not very useful by 22%, not at all useful by 12%, not applicable to my work by 12% and 9% did not know.

Screening tools were found to be very useful by 13%, somewhat useful by 31%, not very useful by 21%, not at all useful by 6%, not applicable to my work by 19% and 10% did not know.

The CBSA 24-hour telephone support line was found to be very useful by 8%, somewhat useful by 9%, not very useful by 12%, not at all useful by 16%, not applicable to my work by 28% and 32% did not know.

Based on survey results and key informant interviews, there is a need to keep tools, policies, and procedures more up-to-date. Although nearly half of all respondents (48%, see Table 9) indicated that the tools, policies, and procedures they use are kept up-to-date so they remain relevant to their work, over half of all the CBSA respondents (13 out of 22) indicated their tools, policies and procedures were not kept up-to-date. These respondents commented on the need for updated manuals (such as the CBSA Enforcement Manual, and the Tactical Guide to Canada’s CAHWC Program), foreign contact lists, and country profiles. The CBSA reports that specific chapters of training material are updated on an as-needed basis when there is a change in policy. More comprehensive reviews of these resources occur less frequently. The Enforcement Manual was last updated in 2005, although during the evaluation it was in the process of being updated, and the Tactical Guide is from 2009. Key informants noted that the operational bulletins are intended to supplement the manuals until they are updated, but some thought that a ten-year period between reviews was excessive.

| Response | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 30 | 48% |

| No | 17 | 27% |

| Not applicable to my work | 6 | 10% |

| Don't know | 9 | 15% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Base: Respondents who have used at least one tool, policy, or procedure

Based on interviews, Justice counsel, particularly less experienced counsel, desire clearer policies on their role and more guidance on how to approach their work (e.g., they wish to know who has authority over different aspects of a file, when to contact the IAG within Justice). They also wanted more technological support, such as litigation support software applications, including an updated Ringtail.

For the RCMP, the types of support that interviewees indicated are most important to their Program-related work are the specialized policing services such as forensic anthropologists, ballistics experts, and crime scene re-creation experts. According to RCMP interviewees, the greatest impediment to continuity in police investigations is the limits on resourcing options to engage translators in support of investigations. The Public Service Employment Act rules on casual employment restrict hiring for more than 90 days in one calendar year. It is difficult for the investigative team to source a security-cleared interpreter/translator of a specialized language for the duration of the investigation.

The Program has undertaken knowledge management activities, but capacity to develop a coordinated approach has been an issue

Training materials, tools, policies, and procedures discussed above constitute some, but likely not all, of the information assets of the Program. Knowledge management involves capturing, organizing, and sharing this type of information. Generally speaking, knowledge management is considered important to improve the effective and efficient operation of a program, as well as to manage risks associated with the potential loss of expertise that will occur when employees retire or leave the related position.

The Program has undertaken some activities related to knowledge management. Although Program partners continue to collect and develop information, efforts to develop a shared repository of CAHWC information have stalled or become dormant. Probably the most comprehensive attempt at developing a central repository of data, literature, documents, and other materials relevant to the Program was the CBSA Modern War Crimes System (MWCS). According to CBSA key informants, this system fell into disuse for a number of reasons, including loss of funding and personnel (it was labour-intensive to update and maintain), lack of awareness of MWCS (personnel turnover), and the rise of the Internet, which led to staff doing searches on their own for publicly available material.

Other efforts at knowledge management that were undertaken at the PCOC level include:

- The Research Committee

- This committee was intended to build a bridge between Justice and the CBSA. However, it last met in March 2011. While an annual event on sharing research was planned, it does not appear to have occurred.

- The Virtual Library Project

- This project was announced in 2008 as a means of improving the coordination of the Program’s research capacity. Key informants stated that such a tool would be particularly useful because it would allow agencies to share their paper-based archives and list their research products produced over the past decade. The idea was revived in 2013 under the auspices of the Enhanced Cooperation Subcommittee of PCOC. However, based on Program documentation, plans have not progressed beyond the discussion stage.

- The Standardized Training Committee

- This committee’s mandate was to come up with products that can be used by all Program partners for training purposes. To date, the Committee has not produced any products or curricula due to lack of funding to support this work. As of 2013, the work of this committee was put on hold.

- PCOC

- Had committed to maintain a calendar of training and outreach activities, which could be used to document and link to training materials. However, it does not appear that this calendar was developed.

- The War Crimes Program Website

- The website was completed in 2010, but no major refresh of its content has occurred in the last five years. The website is both a knowledge management and an outreach tool. As will be discussed under Outreach, external stakeholders have noticed the staleness of the website.

In general, the level of coordination of knowledge management anticipated in the Program’s logic model (see Appendix A) is not evident from Program activities, which has also meant that some recommendations from the 2008 evaluation remain unaddressed. For example, a coordinated training plan was recommended in the 2008 evaluation and is indicated as a Program output under Knowledge Management; however, the Standardized Training Committee, which appeared to be tasked with developing that plan, has been placed on hold. According to its logic model, the Program also expected to undertake “administrative measures to promote proper recording, preservation, sharing, and transfer of operational/relevant information and records” (Department of Justice Canada, CBSA, RCMP, and CIC, 2013). As noted above, the MWCS, which the 2008 evaluation recommended improving and upgrading, is dormant. In addition, the lack of a centralized research database has resulted in a lack of coordinated research efforts, with the four Program partners independently conducting open-source research, creating substantial overlap, according to a few key informants. Given that the Program emphasizes its multi-disciplinary, coordinated approach as a major benefit, the lack of a coordinated training plan and a centralized research repository appears to be a major gap in its knowledge management efforts.

Outreach activities are ongoing, but could potentially be more coordinated and targeted

The Program’s outreach activities are intended to increase the knowledge and awareness of the Program by populations with a particular interest in crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide (e.g., NGOs that work in the area, organizations that assist diaspora communities, other countries that want to learn from the Program’s experience) as well as the general public. The evaluation findings indicate that the Program partners have individually participated in outreach activities during the evaluation period. Notably, few of these activities targeted the public. Examples of the type of outreach activities are listed below:Footnote 20

- Justice representatives attending the EU Genocide Network, which is considered good for sharing best practices and learning from other countries

- Program partners making presentations at various conferences, schools, and universities

- the Program’s public presence with website and annual reports

- meetings with other countries (e.g., the United States) to share best practices

- training for other countries (e.g., the CBSA conducted training in Islamabad, Pakistan)

- the CBSA workshop on war crimes intelligence (see discussion under training, above), which was attended by other countries and NGOs in addition to Program partners

- Justice working with NGOs and academic institutions to deliver courses on the CAHWC Act

- RCMP contribution to best practices to international police colleagues through attendance at INTERPOL and Europol symposia on CAHWC

- the CBSA’s current Intelligence and Analysis Section’s weekly publication related to contemporary war crimes, which is used as an outreach tool within the CBSA, IRCC, and international partners

- an outreach plan developed by the RCMP and Justice, which involved the creation of a pamphlet and work with diaspora communities from Rwanda and the Balkans

- media coverage of CAHWC prosecutions, which serves as a form of outreach

While outreach continues to occur, the evaluation found that the Program has not followed through on suggestions to address identified gaps, such as developing a combined outreach plan among partners and conducting more outreach to groups in Canada, both of which were raised in the 2008 evaluation as well as in 2010 at PCOC. Coordination of outreach may be affected by the decision to forego discussions on outreach at each PCOC meeting and instead use a calendar to record these activities; the calendar of outreach and training events, as noted above in the section on training, has not been developed. Also, in 2010, PCOC established the Education Needs and Outreach Committee, led by Justice and the RCMP, which would be responsible for promoting the Program, providing presentations, and producing products.

Some Program key informants still believe the Program needs to do more outreach with victim communities on a proactive and timely basis. According to Program key informants, the Program’s initial efforts to do outreach with Rwandan and Balkan diaspora communities did not work well and there was a lack of response from these and other target communities. However, the Program has continued to consider options in this activity area. In particular, over the past year, the Program has been considering options, around how best to reach Syrian refugees with information about the Program.

Survey and interview findings also indicate that outreach is an area for improvement. When asked to rate the level of awareness of international and domestic stakeholders who deal with human rights abuses, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, less than one-third of survey respondents believe these groups are very aware of the Program, although most respondents believe these groups are at least somewhat aware. One-quarter of survey respondents believe that the public is at least somewhat aware. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Awareness of Program stakeholders (n=68)

Q12: How would you rate the awareness of the Program and its aims among the following groups…?

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Figure 2: Awareness of Program stakeholders (n=68) - Text Version

Q12: How would you rate the awareness of the Program and its aims among the following groups…?

International organizations that deal with human rights abuses, war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide were thought to be very aware of the Program by 25% of survey respondents. They were thought to be somewhat aware by 40% of respondents, somewhat unaware by 3%, very unaware by 7% and 25% of survey respondents did not know.

Canadian organizations that deal with human rights abuses, war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide were thought to be very aware of the Program by 29% of survey respondents. They were thought to be somewhat aware by 34% of respondents, somewhat unaware by 7%, very unaware by 6% and 24% of survey respondents did not know.

Representatives of agencies working in related areas in other countries were thought to be very aware of the Program by 13% of survey respondents. They were thought to be somewhat aware by 40% of respondents, somewhat unaware by 19%, very unaware by 3% and 25% of survey respondents did not know.

Non-governmental organizations that assist victims and communities that have experienced war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide were thought to be very aware of the Program by 16% of survey respondents. They were thought to be somewhat aware by 35% of respondents, somewhat unaware by 7%, very unaware by 13% and 28% of survey respondents did not know.

The public was thought to be very aware of the Program by 1% of survey respondents. They were thought to be somewhat aware by 24% of respondents, somewhat unaware by 26%, very unaware by 26% and 22% of survey respondents did not know.

In addition, most survey respondents who offered opinions do not believe that outreach efforts to raise awareness with domestic or international stakeholders are sufficient (see Table 10).

| Statement | Agree | Somewhat agree | Somewhat disagree | Disagree | Not applicable to my work | Don't know | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| The outreach efforts to raise awareness with international stakeholders are sufficient | 3 | 4% | 7 | 10% | 8 | 12% | 15 | 22% | 10 | 15% | 25 | 37% |

| The outreach efforts to raise awareness with domestic stakeholders are sufficient | 1 | 1% | 8 | 12% | 12 | 18% | 19 | 28% | 8 | 12% | 20 | 29% |

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Note: Row totals may not sum to 100%, due to rounding.

Key informant opinions aligned with and provided additional context for the survey findings. Program key informants reported that the Program has done some outreach work, such as working with NGOs and academic institutions to deliver courses on the CAHWC Act, and with diaspora communities, who can be a viable source of complaints, but they also noted more could be done. Academic and NGO key informants believed more Program outreach to domestic and international NGOs would help increase knowledge of the Program. They also suggested greater outreach with victims/survivors and victims’ organizations to ensure diaspora communities are aware of the Program and how it works.

Online publications through the Program’s website (annual reports, press releases) and/or publications by Program experts in crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide were a commonly recognized form of Program outreach. However, both Program and external key informants pointed out that the website has had few updates since 2010, and that the annual report for the Program has not been available for a number of years; as such it remains an inadequate vehicle for communicating with the external stakeholder groups and the general public.

4.2.2. Effective allegation management

According to the Program’s performance measurement strategy, allegation management is “the way in which the Program partners determine the disposition of cases” (Department of Justice Canada et al., 2013). There are several possible dimensions to allegation management, including identifying and screening allegations, investigating allegations, selecting and implementing remedies, and monitoring outcomes.

The evaluation findings indicate that, in general, the Program has effectively managed allegations; however, the limited knowledge of the Program as a whole among key informants and survey respondents lessens the strength of this finding. Many interviewees from partner departments could only comment on aspects of managing allegations in which they were directly involved. Some of these interviewees, but especially NGOs and academic key informants, said their ability to assess the effectiveness of allegation management was limited given the lack of up-to-date performance reporting and outcome information for the Program.

The Program is considered effective in identifying and screening allegations

Identification and screening allegations are considered important aspects of allegation management as they can send a message to individuals who have been involved with or complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide and to their networks (which may include other war criminals) that Canada will not provide a safe haven. Key informants from across the stakeholder groups (Program, international peer community, NGOs, and academics) recognized the importance of IRCC and the CBSA’s admissibility screening, and some described Canada’s approach to screening as very effective and advanced compared to other jurisdictions. In particular, the standard screening tools/questionnaires/protocols used by IRCC and CBSA staff for screening asylum seekers were noted as innovative and best practices that other countries should learn from and emulate.

A few key informants pointed out that conflicts that give rise to crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide can be localized and require very specialized knowledge of the region and the conflict in order to identify those who may have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. Program partners believe that tools are assisting with identification and screening for involvement or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, although there is interest in more training and updated tools (see Section 4.2.1). In addition to tools, collaboration among partners such as the CBSA, working with experts at Justice to ensure the CBSA’s screening took into account region specific-conflicts, helps ensure this step in allegation management is effective.

The Program is considered to conduct well-organized, detailed investigations of allegations, but resource constraints remain an issue

Few external stakeholders could comment on the effectiveness of the Program in investigating allegations, but those who did commended the RCMP for their well-organized, detailed, and well-executed investigation plan. All key informant groups noted the resource-intensive nature of CAHWC investigations. Several key informants (particularly Program partners, but also international peer organizations) raised concerns about the resource constraints of the RCMP, and how these constraints are affecting the number of active investigations that the RCMP can conduct. The RCMP position is that criminal investigations are prioritized and pursued in keeping with the Program’s capacity to pursue criminal investigations and prosecutions. The 2008 evaluation recommended funding to increase the investigative capacity of the RCMP. The resource demands on the RCMP are well beyond the CAHWC funding received; it was noted that expenditures exceeded the available Program allocation by between 50% and 150% (fiscal years 2010-11 to 2012-13). Justice has recently worked with the RCMP to reduce the criminal inventory by shifting files to IRCC and Justice to pursue immigration remedies, which is hoped to reduce the investigative burden on the RCMP.

RCMP and Justice work closely on investigations and recognize the need to have effective coordination

Both RCMP and Justice key informants spoke of the closeness of their working relationship on these investigations, as they can persist for years. They also acknowledged that the working relationship between the departments remains a work in progress. Several issues were mentioned:

- Coordination between Justice and the RCMP regarding the active criminal inventory could be improved. There have been situations in which priorities regarding which files should be active are not aligned, and files are pursued that the other partner has not prioritized and/or has closed. Key informants suggested that the RCMP and Justice need to communicate better on what files are priorities.

- RCMP key informants believe that investigations for the CAHWC Program could be improved and made more efficient by earlier and/or more direct involvement of the PPSC. Currently, the Justice CAHWC Section works directly with the RCMP on the investigations. Justice key informants noted that the cost of earlier involvement of the PPSC was a factor in the timing and type of involvement PPSC has on files that are being investigated.

- Both Justice and RCMP interviewees believe that Justice’s CAHWC Section would benefit from having more counsel with more experience in criminal litigation.

- The role of counsel in investigations was raised as an area that has, at least in the past, created tension. The level of Justice counsel involvement in investigations appears to vary by counsel and file, and may not always recognize that the RCMP is both the lead and the client on the file. As a result, a few key informants noted that Justice’s work products may not be seen as adding value to the investigation. Counsel desired greater clarity with respect to their role so that they would not be duplicating work or overstepping their authority in making information requests related to criminal investigations.

The File Review Subcommittee and criteria used to select remedies and prioritize files are considered effective

The selection and implementation of remedies was identified as an area where the Program had demonstrated improvement during the time period covered by the 2008 evaluation. Based on Program documents, to use limited resources most effectively and handle the volume of potential matters, the Program established a priority for using remedies. The highest priority is given to prevention remedies, which are to deny overseas visa applicants for whom there are reasonable grounds to believe they committed or were complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. Second priority is given to the immigration remedies (i.e., refugee exclusion, admissibility hearings, and deportation proceedings). Citizenship revocation and criminal prosecutions, which rely heavily on thorough investigations for the evidence to support them, are considered critically important remedies, but are used selectively given the resources these remedies require. Criteria for determining which files are selected for the criminal inventory are adjusted depending on emerging pressures facing the Program, but they include factors such as seriousness of allegations, the presence of victims in Canada, and the returnability to the countries of origin.Footnote 21 Program key informants commented that the file review process has continued to improve, and they generally believe that the Program is making the best decisions regarding how to direct its resources.

The focus on prevention and immigration remedies received criticism from some stakeholder groups

All key informants emphasized Canada’s continued commitment to addressing allegations of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide through the Program. While acknowledging the cost of conducting criminal investigations leading to prosecutions for these crimes, some external (international peer community, NGOs, and academics) and Program key informants expressed a desire for the Program to attempt more prosecutions. These key informants criticized the emphasis on immigration remedies, as they view these remedies to be less effective in holding individuals who have committed or are complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide accountable.

Key Program strengths in allegation management are the multi-departmental approach and the expertise of staff

Many key informants across the stakeholder groups mentioned the Program’s multi-departmental approach, which brings together expertise and information across multiple disciplines as contributing to effective allegation management. Bringing individuals together from the partner departments and agencies was considered important to properly assess which remedy is appropriate. In addition, many key informants referred to the quality and expertise of Program staff, describing these individuals as world-class, knowledgeable, motivated, and very committed to their work. A few key informants highlighted the importance of having long-term or specialized staff working for the CAHWC Program, since these roles lead to cumulative knowledge and expertise.

Sharing information among partners is an important element of successful allegation management

As shown in the process flows for the remedies (see Appendix D), each remedy can involve multiple Program partnersFootnote 22 and different remedies may be used sequentially in some situations. As a result, the working relationship among the partners is a key element affecting effective allegation management. Key informants from partner departments and agencies generally praised the working relationship among Program partners, often commenting positively on the regularity of communications and meetings among partners.

Many of these key informants also referred to challenges related to sharing information within a multi-departmental/multi-jurisdictional environment. They explained that each Program partner stores their case information in separate databases, which, for structural and legal reasons, are not directly accessible to other Program partners. To work around this challenge, Program partners have developed different strategies to indirectly share case information, with mixed success.

For example, Justice and IRCC have developed a mechanism to facilitate locating and retrieving relevant case information, when appropriate, through a part-time IRCC liaison that is stationed in the CAHWC Section of Justice (although is still an employee of IRCC). Key informants from Justice explained that the liaison makes retrieving immigration files and information from IRCC faster and easier. These key informants believe this role has been tremendously helpful and has improved the relationship between IRCC and Justice. They desire to maintain this arrangement.

Another example of indirect sharing are the file transfer protocols developed between the RCMP and Justice and between Justice and the CBSA to indirectly transfer investigations from the RCMP to the CBSA through Justice. This happens in cases where there was insufficient information to further pursue criminal investigations, but still potential for the CBSA to pursue regulatory enforcement. The protocol involves the RCMP transferring case information to Justice, who then vets the information and provides the CBSA with information deemed releasable under privacy legislation. However, the CBSA key informants reported that the information provided is frequently missing important background information, which could assist the CBSA in making presentations to the IRB. As a result, the CBSA regional staff must conduct their own investigation which, according to the CBSA key informants, is duplicative and lacks the scope and detail that would come out of RCMP or Justice investigations.

RCMP key informants were frustrated by the amount of time it takes to transfer information domestically and internationally, and were concerned about the potential for Program and international partners to be duplicating efforts. These key informants suggested integrating domestic resources through a joint task force or by co-locating Program partners.

Case studies were a useful source for more specific operational information on how the partners work together. In case studies, some issues arose in terms of getting information from other partners in a timely manner (e.g., requests from RCMP to the CBSA or IRCC for information to support investigations).

Monitoring outcomes is identified as an area for improvement

Program key informants believe more regular performance reporting would create more accountability within the Program. Other key informants (NGOs, academics) also mentioned the lack of regular performance reports available online. A few key informants from partner departments/agencies also want the Program to conduct more monitoring of outcomes. There is the desire for internal reporting that tracks decisions in files and provides a feedback loop so that, for example, the final decision on screening for files on which it was consulted is relayed to the CBSA.

Overall assessment in allegation management

Survey findings indicate that the Program is successful in implementing most remedies. Those respondents who could provide an opinion believed that most remedies have been successfully implemented by the Program. The prosecution remedy was the one exception. Based on key informant findings discussed above, this assessment of the lack of success in implementing prosecutions is likely due to the small number of prosecutions and the resource constraints that limit the ability to pursue this remedy.

Figure 3: Success in implementing remedies (n=68)

Q15: To what extent has the Program been successful in the following activities as related to persons believed to have committed or been complicit in war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide…?

Source: Survey of departmental staff

Figure 3: Success in implementing remedies (n=68) - Text Version

Q15: To what extent has the Program been successful in the following activities as related to persons believed to have committed or been complicit in war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide…?

The Program was thought to have been very successful in denying refugee status by 9% of survey respondents, somewhat successful by 47%, somewhat unsuccessful by 13%, very unsuccessful by 3%, it was not applicable to my work for 12%, and 16% did not know.

The Program was thought to have been very successful in removing individuals from Canada under IRPA by 6% of survey respondents, somewhat successful by 49%, somewhat unsuccessful by 15%, very unsuccessful by 4%, it was not applicable to my work for 12%, and 15% did not know.

The Program was thought to have been very successful in denying visas by 13% of survey respondents, somewhat successful by 40%, somewhat unsuccessful by 9%, very unsuccessful by 3%, it was not applicable to my work for 16%, and 19% did not know.

The Program was thought to have been very successful in revoking citizenship by 10% of survey respondents, somewhat successful by 37%, somewhat unsuccessful by 16%, very unsuccessful by 4%, it was not applicable to my work for 10%, and 22% did not know.

The Program was thought to have been successful in extraditing upon request by other countries by 25% of survey respondents, somewhat unsuccessful by 15%, very unsuccessful by 4%, it was not applicable to my work for 21%, and 35% did not know.

The Program was thought to have been very successful in prosecuting by 1% of survey respondents, somewhat successful by 35%, somewhat unsuccessful by 22%, very unsuccessful by 15%, it was not applicable to my work for 10%, and 16% did not know.

4.2.3. Deterring and preventing persons believed to have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide from entering Canada

While there is no definitive evidence on whether the Program has deterred persons who have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide from entering Canada, Canada has denied about 2,800 visas due to reasonable grounds for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide since 2003–04. As discussed in Section 4.2.2., key informants and survey respondents consider IRCC and the CBSA screening processes to be effective in denying visas to persons believed to have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide to prevent them from coming to Canada. Some key informants pointed out that the denial of visas sends a message to individuals who have been involved with or complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide and their networks (which may include other war criminals) that Canada will not provide a safe haven. Similarly, while key informants could not comment specifically on the deterring effect of Canada’s CAHWC prosecutions, many academic, NGO, and international key informants generally believe that prosecutions deter perpetrators from traveling to jurisdictions that will prosecute these crimes.

The Program performance data show that the number of visas assessed overseas and denied because of reasonable grounds to believe the applicant committed or was complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide has varied somewhat over the last decade, as might be expected based on variations in immigration patterns, but has averaged about 2,700 visa applications per fiscal year. As shown in Table 11, in the time period covered by this evaluation for which data are available (FY 2009–10 to 2013–14), the number of applications assessed overseas for crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide has fluctuated per fiscal year. The number of visa applications denied for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide has declined substantially in the last three fiscal years for which data are available. In the previous five-year period (FY 2004–05 to 2008–09) a total of 1,867 visas were denied, compared to 701 visas in the most recent five-year period for which there is data. This decline is not reflected in the volume of visas assessed and, therefore, could be based on policy and operational factors and which populations apply for visas in a given year. The evaluation cannot speculate on the factors that might explain the decline in visa refusals based on commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

| 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15Table note iii | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary resident visa | 1,969 | 2,480 | 2,879 | 1,883 | 2,053 | 2,953 | 2,864 | 2,418 | 3,791 | 2,675 | 2,397 | n/a | 28,362 |

| Permanent resident visa | 331 | 171 | 145 | 146 | 191 | 197 | 371 | 216 | 39 | 103 | 184 | n/a | 2,094 |

| TOTAL | 2,300 | 2,651 | 3,024 | 2,029 | 2,244 | 3,150 | 3,235 | 2,634 | 3,830 | 2,778 | 2,581 | n/a | 30,456 |

| Total deniedTable note ii | 242 | 385 | 367 | 361 | 326 | 428 | 269 | 215 | 45 | 97 | 75 | n/a | 2,810 |

| % denied | 11% | 15% | 12% | 18% | 15% | 14% | 8% | 8% | 1% | 3% | 3% | n/a | 9% |

Source: Program data.

- Table note ii

-

According to the Program performance reports, this number includes visa applications denied because of reasonable grounds to believe the applicant committed or was complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide; applicants who withdrew their visa applications when asked for more information during screening; and applications denied for other reasons, even though there were reasonable grounds to believe the applicant committed or was complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide.

- Table note iii

-

n/a – data not available

A few key informants noted that there is not a feedback loop for the Program to understand how individuals screened for crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide and who are declared eligible to enter Canada are later found in the inventory for immigration, criminal investigation/revocation, or investigation/prosecution remedies. This information would indicate how successful the Program is in preventing persons who have committed or are complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide from entering Canada.

4.2.4. Removing persons believed to have committed or been complicit in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide

Once individuals suspected of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide have entered Canada or are seeking refugee status from within Canada or at a port of entry, the Program has various remedies that, if successful, may ultimately result in their removal.

Assessing Program performance with the available data, as demonstrated in the sections that follow, is difficult. The performance data are based on annual totals for each remedy in isolation from each other, which limits the ability to assess success by knowing, for example, what proportion of individuals excluded from refugee protection is eventually removed from Canada. In addition, unless the person formally complies with the removal order, the Program does not know whether the individual has left Canada. In some cases, individuals with removal orders may leave the country without notifying officials.

With these limitations in mind, the Program performance data show a pattern of use of the remedies that align with the emphasis on immigration remedies over those of citizenship revocation and prosecution.

Exclusion from refugee status

As described in Section 2.4., the CBSA can intervene in refugee claims before the IRB that raise concerns about the claimant’s possible involvement in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. If the IRB finds a person excluded from refugee protection, the CBSA may initiate admissibility proceedings for a finding of inadmissibility under s. 35 of IRPA or directly initiate removal proceedings where a removal order exists and is in force.

Based on performance data, both the number of refugee claims investigated for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide and the number of interventions filed by the CBSA have varied year to year, which may be due to a variety of factors, including variations in volume of refugee claims and countries of origin of individuals claiming refugee status.

Using the previous six-year period (2003–04 to 2008–09) as a baseline and comparing it to the six-year period covered by the current evaluation (2009–10 to 2014–15) shows that the number of exclusions and denials as a proportion of total interventions has increased from 55% to 63%. This result must not be interpreted as the percentage of successful interventions. For each six-year period, some refugee claims in which the CBSA had intervened would be ongoing and some decisions made by the IRB would be based on interventions initially filed before the six-year period. That said, the number of war crimes-related exclusions and denials of refugee protection as a proportion of total interventions in which the CBSA has challenged refugee status on the basis of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide is an indication of success (as seen in Table 12).

The data also appear to reflect the impact of the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Ezokola v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), [2013] 2 SCR 678, which changed the test for assessing whether a claimant should be denied refugee status because of involvement in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. The Supreme Court of Canada rejected the idea that exclusion under Article 1F(a) of the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugee Convention) can be made based on “mere association”, and instead required evidence that an individual has made “a voluntary, knowing and significant contribution to the crime or the criminal purpose of a group.”

| 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Refugee claims investigated by the CBSA for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide | 883 | 2,024 | 1,373 | 1,395 | 612 | 549 | 794 | 680 | 602 | 503 | 365 | 445 |

| Number of Interventions for exclusion filed by the CBSA for commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes or genocide | 387 | 155 | 237 | 82 | 80 | 112 | 87 | 88 | 103 | 59 | 77 | 41 |

| Cases excluded from refugee protection (reasonable grounds to believe commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide) | 63 | 79 | 40 | 31 | 26 | 18 | 25 | 31 | 37 | 34 | 8 | 5 |

| Cases denied protection for reasons other than crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide where an intervention for exclusion was filed | 107 | 75 | 53 | 36 | 34 | 19 | 24 | 27 | 15 | 31 | 38 | 10 |

Source: Program data.

Admissibility hearings

Admissibility hearings before the IRB occur when foreign nationals or permanent residents who are already in Canada have become subject to allegations of crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. If the person is a refugee claimant, the refugee claim is suspended pending the outcome of the admissibility hearing. A member at the IRB hears the case and decides whether the person should be allowed to remain in Canada. The volume of admissibility hearings is small and has declined over the last six years (2009–10 to 2014–15). The number of cases under investigation at the end of each fiscal year has also declined for refugee claimants in the last six years compared to that of the previous six years. The evaluation cannot speculate as to the reasons for the decline. See Table 13 and Table 14.

| 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearings opened | 8 | 27 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Claimant found inadmissible and ordered for deportation (reasonable grounds to believe commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide | n/a | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Claimant found not inadmissible following hearing regarding crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide | n/a | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Cases still under investigation at end of FY | 115 | 65 | 27 | 23 | 31 | 16 | 30 | 28 | 33 | 37 | 54 | 41 |

n/a — data not available

Source: Program data.

| 2003-04 | 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearings opened | 8 | 11 | 22 | 12 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Claimant found inadmissible and ordered for deportation (reasonable grounds to believe commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide | n/a | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 3 |

| Claimant found admissible following hearing regarding crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide | n/a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Cases still under investigation at end of FY | 883 | 663 | 346 | 691 | 701 | 161 | 118 | 132 | 232 | 105 | 80 | 35 |

n/a –data not available

Source: Program data.

Removals

Persons who are excluded from refugee protection or have otherwise been found to be inadmissible are subject to the removal process, which can lead to removal from Canada. Removing individuals from Canada is a complex process. The performance data reflect this complexity, as over the last 12 years, there remains a sizeable pending inventory of enforceable removal orders.

With the exception of 2011-13, the performance data show a general decline in removals since 2006–07. From 2003–09, there were 207 removals and from 2010–15, there were 138 removals on the ground of involvement or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. In addition, at the end of 2014–15, there were 181 outstanding warrants for removal of these individuals. Immigration warrants are issued when an individual does not report for removal or for other immigration proceedings, such as admissibility hearings. The difficulty with assessing Program performance on the basis of outstanding immigration warrants is that individuals may leave Canada without notifying the CBSA, and since Canada has no exit controls, the Program does not know how many of the individuals with outstanding warrants may have already left.

Figure 4: Removals inventory

Figure 4: Removals inventory - Text Version

| Fiscal Year | Number of successful removals for CAHWC-related cases | Number in the pending inventory of enforceable removal order for CAHWC-related cases | Number of unenforceable removals (stayed, travel documents, PRRA) | Number of outstanding warrants for removal for CAHWC-related cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003-04 | 44 | Not available | 145 | 125 |

| 2004-05 | 42 | 72 | 148 | 134 |

| 2005-06 | 41 | 83 | 98 | 154 |

| 2006-07 | 35 | 59 | 81 | 162 |

| 2007-08 | 23 | 103 | 109 | 170 |

| 2008-09 | 22 | 97 | 96 | 177 |

| 2009-10 | 22 | 99 | 128 | 172 |

| 2010-11 | 17 | 199 | 207 | 177 |

| 2011-12 | 24 | 38 | 148 | 176 |

| 2012-13 | 41 | 123 | 113 | 172 |

| 2013-14 | 17 | 102 | 104 | 177 |

| 2014-15 | 17 | 74 | 98 | 181 |

Revocation of citizenship

This remedy operates through the Citizenship Act, which enables the government to revoke the citizenship of persons who obtained their citizenship through misrepresentation, fraud, and knowingly concealing material circumstances. This remedy is used as part of the CAHWC Program when an individual fails to disclose information related to commission or complicity in crimes against humanity, war crimes, or genocide. Once citizenship is revoked and all appeals are exhausted, a person reverts to their former status as a permanent resident or foreign national and may be subject to an admissibility hearing and removal.