Victims of Crime Research Digest No. 12

Testimonial Aids Knowledge Exchange: Successes, Challenges and Recommendations

By Shanna Hickey and Susan McDonald

In March 2018, the Department of Justice Canada (Justice Canada) hosted a Knowledge ExchangeFootnote 100 in Ottawa on testimonial aids, with about 80 participants from across the country and from across the criminal justice system. Justice Canada sought high-level input from the participants of the event on their successes, challenges, and recommendations on the use of testimonial aids for vulnerable witnesses. This article provides the results of that input.

Canada has included provisions in the Criminal Code (CC) allowing witnesses to use testimonial aids since 1988, when former Bill C-15 (An Act to amend the Criminal Code of Canada and the Canada Evidence Act) came into force. Further amendments came into force in 1999, 2006, and, most recently, in 2015, with the Victims Bill of Rights Act (VBR). This article complements the review of social science research in the Victims of Crime Research Digest, No. 11 (McDonald 2018) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how testimonial aids are being used in Canada.

As noted in McDonald (2018, 5):

There are three types of testimonial aids: a witness may testify from behind a screen, from outside the courtroom via closed-circuit television (CCTV), or alongside an accompanying support person. In addition to these traditional aids, the Criminal Code and the Canada Evidence Act also authorize publication bans and video-taped testimony, along with appointment of counsel to cross-examine a witness and orders to exclude the public from the courtroom.

Seeking Input

Using an online survey, Justice Canada sent four qualitative questions to the participants of the Knowledge Exchange before the event. It then analyzed the answers for themes, that were presented during the one-day event. No participants were identified in the results.

What Participants Said

Thirty-two respondents contributed to the survey: 50% (n=16) worked in victim services; 28% (n=9) were legal counsel (including Crown prosecutors, defence, etc.); 13% (n=4) worked in governmental policy or programs; and 1 respondent each reported being a police officer (n=1), a judicial educator (n=1), and a worker at a Child Advocacy Centre/Child and Youth Advocacy Centre (n=1).

Successes

The first question asked respondents to share a testimonial aids success story. Out of thirty (30) responses provided, almost all of them told a story about a case in court where CCTV or video-conferencing was successfully used. A success included the victim/witness being able to testify and provide a full and candid account. A few of these success stories are shared below:

… at a recent sex assault trial one of the victims was literally hyperventilating, having a panic attack outside the court room. She had a panic attack on the drive to court and had to pull over to the side of the road and get a friend to drive her the rest of the way. Once she got to court she realized she knew some of the accused’s friends who were in the court room...this led to the hyperventilation. I made an application for the witness to testify via CCTV. The application was granted. The witness, while extremely nervous, anxious and breathing heavily, managed to complete her testimony and the court convicted the assailant.

Young victim of physical abuse by father. Initially wanted to testify in the courtroom. During her testimony it became clear that she was being less than forthcoming with her evidence. During a break she disclosed to a victim witness worker that her father (accused) was glaring at her and making her uncomfortable. Crown made mid-trial application for CCTV which was granted. Victim testified outside of the courtroom, was full and frank in her testimony and accused was convicted.

In a sexual interference trial, (we were) successful in having a 14 year old victim testify via CCTV with a support person, both of which were required as she was extremely nervous about having to testify. The accused was her uncle and this made the need for testimonial aids even more important as the victim felt her aunt, the accused’s wife, would be very upset by her testimony and seeing her aunt in the courtroom would make it even harder to have to testify from inside the courtroom. A finding of guilt was made based primarily on her testimony.

In a case of human trafficking, the victim was prepared to testify only if she would not have to do so in front of the accused. During a witness prep meeting, the victim provided some information about the accused contacting her, threatening her and pressuring her into providing a recant statement. The victim was fearful. In preparation for the trial, I brought an application for the use of the CCTV room. Defence counsel was contesting the application as it was not a mandatory order. The judge ultimately granted the application. The victim, who will be testifying later this year, was extremely relieved and she is now fully cooperative.

Each of the success stories participants shared met the goal of providing a full and candid account. Other common threads ran through these stories:

- the violent and often sexual nature of the crimes;

- the young ages of the victims/witnesses; and

- victim services working with Crown prosecutors to identify the needs of the victim/witness and to respond to these needs, regardless of whether the specific testimonial aid was available or not.

Although there were many of these success stories, there were also challenges with the use of testimonial aids.

Challenges

Participants were also asked to describe a challenge that they have experienced while using testimonial aids with vulnerable witnesses in the criminal justice system. These challenges included:

- Resistance to the use of testimonial aids;

- Lack of availability/resources;

- Technology issues;

- Process issues; and

- Problems with screens.

i. Resistance to the use of testimonial aids

Forty-five percent of respondents (n=14) reported that Crown attorneys, judiciary as well as defence counsel, resisted using testimonial aids and that this was extremely frustrating. The challenges respondents faced included:

- getting Crowns to request the application, especially for adults or other vulnerable witnesses;

- judges often denying the application for testimonial aids, and

- defence counsel often opposing the application for testimonial aids.

Victims will often be granted a screen in lieu of testifying via CCTV, by secure video link, or videoconferencing. A screen presents its own set of challenges (discussed below). Victim services are concerned they are providing victims with false hope when they tell victims they have a right to request to testify with testimonial aids under the CVBR, because the applications can be denied.

Judiciary feel they receive a more candid account of a testimony if they can see the fear, tears and anxiety. Very disappointing.

The challenge I am facing is the continuous objection by defence counsel of the use of the CCTV room when the order is a discretionary one. Despite the Supreme Court decision in R. v. Levogiannis, some defence counsel continue to raise arguments regarding effective cross-examination, fair trial, etc.

ii. Lack of availability/resources

Thirty-five percent of respondents said (n=11) that testimonial aids are simply not available or are only available on occasion and that there is no consistency across regions. Respondents discussed having to create their own makeshift screen from curtains or room dividers. They also said that fly-in Indigenous communities do not have access to any kind of testimonial aid or victim supports.

iii. Technology issues

Twenty-nine percent of respondents (n=9) said that they experienced technological challenges, primarily challenges with CCTV equipment. Respondents said that either the equipment was not working; the image and sound were not coordinated; the equipment/technology was not available; there were technical difficulties; or that when using CCTV, the camera was left focused on the accused the entire time the victim testified. Others said that court registrars/court staff lacked training and refresher courses, or were not familiar enough with the equipment to be able to operate it properly.

iv. Process issues

Twenty-six percent of respondents (n=8) said that challenges with process issues included the following:

- having to request CCTV equipment 30 days in advance;

- when the identity of the accused is at issue, using testimonial aids does not remove the need for the victim to identify the accused in court;

- using videoconferencing with very young children is sometimes difficult because they are easily distracted;

- some witnesses find testimonial accommodation kits intimidating; and

- having the Crown and defence counsel in a very small CCTV room can be intimidating for victims.

One of our vulnerable (homeless/addicted/indigenous) victims of a serious sexual/aggravated assault was incarcerated under S. 545 of the criminal code ... and transported to and from court ... with the accused person (high risk offender)... The [preliminary] inquiry was well underway (2 days) by the time a “screen” even came up in conversation.

v. Problems with screens

Sixteen percent of respondents (n=5) said that there are challenges when using screens. These include the following:

- their application for screens has been denied;

- testifying with a screen does not reduce anxiety or stress because victims are aware the accused is present;

- screens are ineffective at actually blocking the accused from view; and

- for young children the screen can become a distraction and should be placed in front of the accused instead.

Recommendations

The final survey question asked respondents to provide three recommendations to improve the use of testimonial aids with vulnerable witnesses in the criminal justice system. Five themes emerged. These include:

- Consider amending legislation to:

- provide clarity on the use of support dogs;

- standardize the application process;

- remove discretionary language in the Criminal Code;

- remove preliminary hearings for children;

- Ensure a broader – and more equitable – use of testimonial aids, especially in rural and remote communities;

- Address challenges with the logistics of using testimonial aids;

- Increase resources for the latest technology; and,

- Provide ongoing education/training for professionals as well as public education.

i. Consider amending legislation

Seventeen respondents (57%) recommended changes to the process of applying for testimonial aids, for example, creating a standard process to request a testimonial aid to ensure a decision is made quickly and well before the trial. Other recommendations included:

- writing applications for testimonial aids that can be ordered as desk orders by the court, i.e., no motion would be argued; and

- entering reasons for allowing/denying an application into the record for proceedings.

Respondents had strong, though at times conflicting, recommendations about the role of Crown, judge, and defence counsel. Some suggested that Crown prosecutors should be more open-minded and more willing to make testimonial aid applications. Others recommended that:

- when Crowns do make applications for testimonial aids they need to make them earlier in the process, well in advance of the hearing, to avoid delays and to better prepare victims;

- Crowns sometimes don’t provide enough warning to Court staff that they require the equipment; staff are then unable to provide the testimonial aid;

- Crowns do not have the time or resources to address all the needs of many victims;

- testimonial aids should not depend on the opinion of a Crown or judge; and

- Crowns or judges should have less discretion in the matter.

Some were of the opinion that defence counsel should have less input as to whether the victim should use a testimonial aid, whereas others believed it should be up to defence to demonstrate how using a testimonial aid would interfere with the proper administration of justice.

The use of testimonial aids is wholly dependent upon whether the Crown/judge see value in the victim having such testimonial aid made available. The use of testimonial aids should be on election of a vulnerable victim, not on players within the court room process.

Other respondents recommended that using a testimonial aid should be the decision of the victims and witnesses who have to testify. Many of these recommendations were advocating for the removal of restrictions to testimonial aids, including age, vulnerability, and the legislative language of “may.” Respondents want to be able to use testimonial aids with all victims and witnesses, regardless of age or type of crime, and would like to use testimonial aids at pre-trial and in the early resolution process.

The removal of preliminary hearings – which are not testimonial aids – for children was also recommended, along with removing the need for victims to testify at the application for testimonial aids. Last, it was recommended that the screen and the use of CCTV be made into two separate applications and that a photo of the victim at the age they were victimized be shown in court, especially in cases of historical abuse.

I am of the opinion that mandatory testimonial aid orders should not be limited to witnesses under the age of 18 years old or to witnesses that have a disability. There are offences in the Criminal Code for which there should be mandatory testimonial aid orders for the victims (i.e., sexual assault, human trafficking).

Nine respondents (30%) recommended clarifying the use of support animals and support persons. The suggested recommendations included:

- making support dogs available in all jurisdictions;

- amending the Criminal Code to include using a dog for support;

- including a provision that supports accredited facility dogs;

- creating consistent guidelines for the use of support persons; and

- having greater flexibility about what is considered a support person.

ii. Ensure a broader – and more equitable – use of testimonial aids, especially in rural and remote communities

Sixty percent of survey respondents (n=18) wrote that the use of testimonial aids needed to be more inclusive, more broadly used, and more available among remote, Indigenous communities. Respondents felt that CCTV needed to be available for all victims of crime and that it should be available in all courtrooms. Some recommended that the technology should be set up in every courtroom, ready to go, regardless of how it would be applied. Respondents also felt it was important to broaden the types of available testimonial aids.

iii. Address challenges with the logistics of using testimonial aids

Thirty-seven percent of respondents (n=11) recommended changes to the logistics of using testimonial aids. These included the logistics of screens, CCTV, and seeing the accused in court. The majority of comments about screens were that they need to be improved. For example, some of the recommendations stated that screens be bigger, darker, not placed in front of the victim (as this causes anxiety/claustrophobia/fearfulness), and that they allow the accused to first leave the courtroom so that the victim can enter the courtroom behind the screen, privately.

While screens may be utilized with the best of intentions to shield victims from the gaze of the offender – and that objective is often met – they also serve as degrading props that nonetheless do not minimize trauma / re-victimization or inconvenience. The current times call for a better solution.

For concerns about CCTV, respondents recommended that testimony be given from a separate CCTV room or with a protective screen; that the CCTV be set up in a different building altogether so that the victim and offender would not see each other; that the Crown should have the option to question in either the courtroom or the CCTV room; and that for any victim under the age of 12, the Crown and defence should remain in the courtroom.

Finally, it was recommended that victims should be allowed to enter the courtroom from side entrances where possible, to avoid walking by the accused; and that those who are waiting in a vulnerable-witness waiting room should remain there until the matter is before the court; they should never be brought to the courtroom early.

iv. Increase resources for the latest technology

Twenty-three percent of respondents recommended increasing resources (n=7). Respondents said that not only were more resources needed, more equality in resources was needed as well. Respondents also recommended new and more advanced technology, including secure video links and microphones to be able to hear witnesses.

v. Provide both ongoing education/training for professionals and public education

Forty percent of respondents (n=12) recommended education and training as well as public education about testimonial aids. Training/education was recommended primarily for judges, Crown prosecutors, and court staff. Respondents said that there needs to be sufficient and proper education not only on testimonial aids themselves, but also on CCTV technology, the needs of victims and witnesses, and the stereotypes surrounding the use of testimonial aids. Another recommendation mentioned was for jurisdictions to share information about case law, best practices, and equipment. Respondents’ recommendations for public education included encouraging a culture that supports the use of testimonial aids; ensuring that victims are aware of testimonial aids; and also soliciting feedback to find out how the equipment is working when they use testimonial aids.

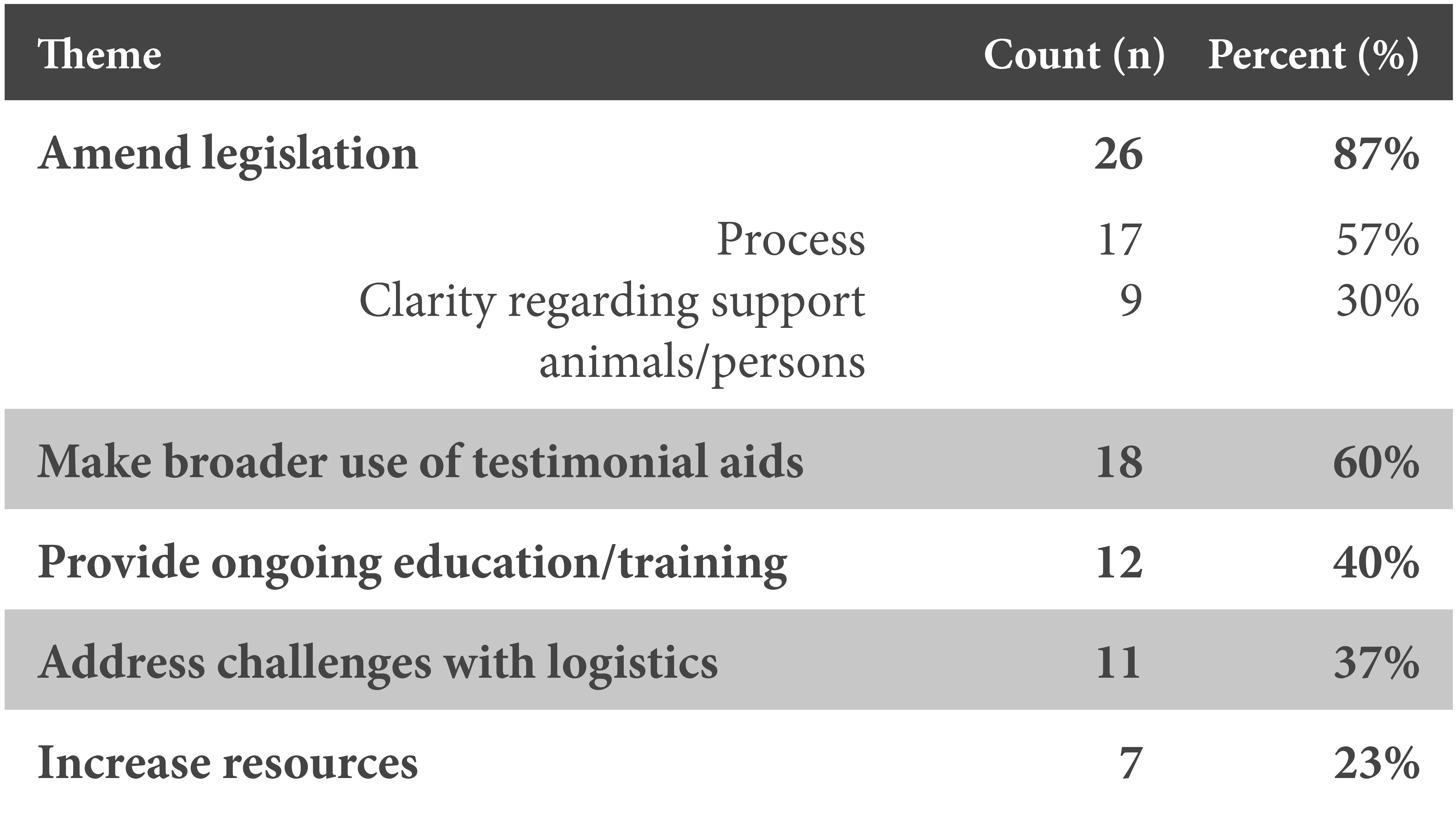

Table 1, below, provides a summary of the five recommendations discussed above. It shows how many respondents identified each recommendation and the corresponding percentage. The table breaks down legislative amendments into two sub-themes, discussed above; when combined it proves to be the recommendation of the five that respondents most supported.

Table 1: Recommendations to Improve the Use of Testimonial Aids (n=30)Footnote 101

Table 1 - Text summary

| Theme | Count (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Amend legislation | 26 | 87% |

| Process | 17 | 57% |

| Clarity regarding support animals/persons | 9 | 30% |

| Make broader use of testimonial aids | 18 | 60% |

| Provide ongoing education/trainings | 12 | 40% |

| Adress challenges with logistics | 11 | 37% |

| Increase resources | 7 | 23% |

Conclusion

It is clear that those who participated in the Knowledge Exchange on testimonial aids see their value and would like to see them used more often and more consistently across the country. Participants recommended amending legislation, providing more training, addressing logistics, and adding more resources to improve the quality of testimonial aid and to reduce the challenges that criminal justice professionals, as well as victims and vulnerable witnesses, are currently experiencing.

References

McDonald, Susan. 2018. “Helping Victims Find their Voice: Testimonial Aids in Criminal Proceedings.” Victims of Crime Research Digest, No. 11, 5–13.

Shanna Hickey is a researcher with the Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada. Her areas of research include victims and restorative justice.

Susan McDonald, LLB, PhD, is Principal Researcher with the Research and Statistics Division, Department of Justice Canada. She is responsible for victims of crime research in the Department and has extensive research experience on a range of victim issues.

- Date modified: