4. Findings

The following section presents the evaluation findings by evaluation issue.Footnote6

4.1 Relevance

4.1.1 Continued Need for the Canadian Family Justice Fund

There is a continued need to support the delivery of family justice services through the CFJF due to the high and increasing prevalence of family violence, high conflict families, and self-represented litigants, and an ongoing need to expand support for mediation, child support recalculation, maintenance and enforcement, and supervised access. Ongoing efforts are required to reach diverse and underserved groups, particularly Indigenous peoples, individuals living in rural and remote communities, newcomers, 2SLGBTQI+ individuals, and persons with physical or mental disabilities.

Divorce rates dropped over the evaluation period; the full impact of COVID-19 will be seen during the next years

Divorce rates provide some indication of the extent of the need for family justice services as they are the only national indicator capturing the rate of family dissolutions. Divorce rates dropped over the evaluation period (2018-19 to 2020-21 from 8.2 to 5.6 divorces per 1,000 married persons) (Figure 1).Footnote7 However, divorce statistics do not include separations and it should be noted that barriers to accessing court services during the COVID-19 pandemic likely contributed to the decrease in divorce applications and granted divorces in 2020. Another factor that delays the impact of the pandemic on divorce rates is that ‘no-fault’ divorce applications, typically the majority of applications, require that a couple separate for at least one year before a divorce is granted. The full impact of disruptions on divorce rates may only begin to be seen in data gathered in 2021, which was not available at the time of this evaluation.

Text version

The above Figure 1 represents the divorce rate in Canada per 1,000 married persons, from 2016 to 2020

The rate, by year, is as follows:

- 2016: 8,6

- 2017: 8,5

- 2018: 8,2

- 2019: 7,5

- 2020: 5,6

Ongoing needs for family justice services remain

The evaluation identified key themes regarding the major needs and trends with respect to family justice services for families experiencing separation or divorce. The most frequently identified needs are as follows:

- Increased need to support those experiencing family violence and high conflict families. From early in the COVID-19 pandemic there were indications of how the pandemic and the public health orders were impacting family violence, and it was referred to as a “shadow pandemic” by United Nations Women.Footnote8 The Ministry of Women and Gender Equality reported in April 2021 that consultations with frontline organizations revealed a 20-30 percent increase in rates of family violence in some regions.Footnote9 The consultations also found that women’s shelters in Vancouver and Toronto reported 300-400 percent increases in calls for assistance. Research has identified a strong correlation between common outcomes produced by such events as isolation, stress, unemployment, increased drug and alcohol consumption, and deterioration in mental well-being and family violence, including lethal violence.Footnote10

- Further, family violence and conflict are taking on a new complexity within the context of the pandemic and increased use of technology. For example, increasingly, abusers are using misinformation and isolation to control survivors socially, physically, and economically. The pandemic forced many families to live together after a separation or divorce due to employment losses or a lack of rental options, contributing to further stress in the household. Further, technology is increasingly being used as a weapon of coercive control, for example, in stalking, social media death threats, and parental alienation claims by accused abusers, which can be used as retaliation to an abuse claim.

- These factors have contributed to an increasing need to support family violence survivors. In order to successfully flee abusive situations, survivors require access to a variety of services such as health, counselling, housing, and supervised access centers, which were diminished during the pandemic.Footnote11 With respect to family justice services, there is a need for public legal education and information (PLEI), parent education programs (e.g., workshops, seminars, and online courses), and other services targeting family violence and high conflict families. As examples, two case studies conducted as part of the evaluation provided evidence of this need:

- The Luke’s Place case study identified that women fleeing abuse require information about how to mitigate safety risks in communicating with their abuser and how to manage the associated trauma.

- The Le Petit Pont case study emphasized the need for information and coaching for high conflict parents to manage their communication, emotions, and stress in the best interest of their child/children.

- Increased need to support self-represented litigants. There is a continuing upward trend of self-represented litigants with 58% of family law litigants in 2019-20 being self-represented.Footnote12, Footnote13 Though many self-represented litigants are above the threshold for legal aid, they still struggle to be able to afford a lawyer, particularly for lengthy litigation. Self-represented litigants can slow court processes and, as such, increase costs for the other party because they are less likely to settle and may not understand the rules of evidence. PT representatives indicated that self-represented litigants use publications, websites, and other PLEI materials and find them to be useful in many cases. However, the accessibility and quality of the information may vary. For example, guidance or support from an information officer may be needed to help self-represented litigants navigate the website and access information. There is a need for family justice services and PLEI to assist self-represented litigants with court processes (e.g., courses, step-by-step guides, flow charts, and checklists).

- Continued need to support and expand mediation, child support recalculation, maintenance enforcement, and supervised access services. Consensual dispute resolution services, such as mediation, are not offered across all jurisdictions (available in 11 out of 13 PTs) and where they are available, they often have long wait times because there are insufficient resources to meet demands. There are long wait times for other services, such as triage, intake or assessment services or dispute resolution services. There is a need to support and expand child support recalculation services (available in 9 out of 13 PTs)Footnote14, which ensure timely and accurate child support payments based on current income levels, without requiring parents to go to court. Maintenance enforcement programs, though available in all 13 PTs, often rely on the CFJF to maintain sufficient PT staff to ensure regular payment of support and the use of enforcement action when cases fall into arrears. Further, support and expansion of supervised access and exchange services (available in 7 out of 13 PTs) is critical for providing a safe, neutral site to support parent and child visits when it is needed.

There are ongoing needs for diverse and underserved groups

The previous Evaluation of Federal Support for Family Justice (2019) highlighted a need to support family justice services targeting diverse and underserved populations. This evaluation identified a continued need to support these groups, particularly Indigenous peoples, individuals living in rural and remote communities, 2SLGBTQI+Footnote15 individuals, newcomers, and persons with disabilities. The Divorce Act amendments also created a need to support PTs with the implementation of a new language rights provision. When implemented in a province or territory, the language rights provision allows individuals to use the Official Language of their choice in a proceeding under the Divorce Act. Almost half of the PTs identified they lacked trained staff to meet the needs of some underserved populations. Additional needs include dedicated funding to allow for services to be tailored to specific groups and regular evaluations of services to ensure that they meet the needs of diverse populations. A continued need to set guidelines and standards and share best practices around how best to target diverse and underserved groups was also highlighted.

The needs with respect to family justice services for specific diverse and underserved groups identified by the evaluation are as follows:

1.8M

Self-identify as Indigenous in Canada

(5% of population)

(2021 Census)

Indigenous peoples. Needs and barriers faced by Indigenous peoples stem from systemic barriers such as racism and colonialism as well as lower levels of educational attainment, higher rates of poverty, and limited access to digital technology (e.g., computers and internet connectivity). The Online Parenting After Separation Course for Indigenous Families case study identified that there is often a lack of awareness among Indigenous peoples about what family justice services and supports are available. Additionally, there is a lack of culturally safe supports available. For example, family justice services offices are often located in courthouses or government buildings and many Indigenous peoples have had traumatic experiences involving courts or government offices (e.g., child and family services) and may be reluctant to access services in these spaces.Footnote16 There is a need for programs that are culturally responsive with culturally competent practitioners and for programs that incorporate and understand the value of family and community working together.

6.6M

Living in Rural

Areas in Canada

(18% of population)

(2021 Census)

Individuals living in rural, remote, and northern communities. Barriers to accessing family justice services for those individuals living in rural, remote, and northern communities include fewer services available (such as mediation services), less timely access to services, increased distance to access services, limited and unreliable transportation, limited childcare, and limited job opportunities, further aggravating economic hardships. The Luke’s Place case study similarly noted challenges in accessing family justice services in rural, remote, and northern communities. For example, judges may fly in once per week or month, and on a rotational basis so there is limited continuity of cases that require several appearances. There are also limited family lawyers. In cases of family violence, an abuser may visit all the lawyers in a small town to prevent the survivor from accessing any of those lawyers since they would be ‘conflicted out’. There are also safety and privacy concerns. For example, a service provider (e.g., police or social worker) may have a relationship with the abuser, further increasing the vulnerability of the survivor.

127K

2SLGBTQI+

couples in Canada

(1.5% of couples)

(2021 Census)

2SLGBTQI+ individuals. Recent research in Western Canada suggests that sexual-minority individuals experience limited access to adequate legal assistance and encounter additional barriers to justice relative to cisgender heterosexual individuals. It was noted that there is a presumption that legal actors are cisgender, heterosexual, monogamously coupled, and part of nuclear family structures, and this presumption is at the base of the family justice system. Further, transgender parents face additional barriers such as misinformation about transgender parents being used in custody cases, challenges being legally recognized as parents due to their transition, a lack of family violence services that cater to transgender individuals, and other barriers due to homophobia and transphobia.Footnote17 There is a need for family justice services that cater to 2SLGBTQI+ individuals such as services delivered by 2SLGBTQI+ individuals, mental health support services, PLEI for legal professionals on the experiences of sexual and gender-minority communities (e.g., pronoun use, HIV stigma, transphobia, homophobia, cisheterosexism, etc.), and PLEI for 2SLGBTQI+ individuals to better understand their rights and how to navigate the family justice system.Footnote18

1.2M

Recent Immigrants

(3.5% of population)

(2016 Census)

Newcomers. Research examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic found that newcomer women of colour involved in family law issues are particularly vulnerable. Within child custody issues, missing child support payments, sexual and physical abuse, and psychological and legal manipulation by the other party were common in three out of four cases. The major barriers to family justice programs and services for newcomer populations include legal and English/French literacy, limited computer literacy, limited access to computers/technology, low levels of income, isolation, a lack of information available, managing facing multiple legal problems, discrimination, fear of consequences from seeing legal action, low perceived chance of success, and a lack of culturally sensitive services.Footnote19, Footnote20 To address these barriers, there is a need for increased access to information, plain language information, increased availability of experts, including, but not limited to, legal, human rights, immigration, and human resources professionals, increased awareness of community resources, and PLEI in the first language of immigrant communities.Footnote21

6.2M

Persons with Disabilities

(22% of population)

(2017 Statistics Canada)

Persons with physical or mental disabilities. Recent research on the experiences of people with physical or mental disabilities found that divorce and family law disputes were included in the list of key types of legal problems encountered. The research highlighted that when facing legal problems, persons with physical or mental disabilities face systemic barriers and a lack of accessible supports such as sign language interpreters for individuals with a hearing impairment. COVID-19 exacerbated existing barriers to justice for people with physical and mental disabilities such as isolation, lack of work income, and limited access to healthcare services.

CFJF Responsiveness to Needs

The CFJF was generally responsive to the current and emerging needs. There is a low likelihood that activities/projects would have proceeded as planned in the absence of the CFJF.

The evidence suggests that the CFJF was responsive and flexible in meeting the needs of PTs and NGOs in their regions with respect to family justice services. Funding allowed PTs to tailor activities to their region’s needs and to raise awareness about family justice information such as changes to the Divorce Act. The CFJF allows Justice Canada to fulfil its responsibility by contributing financial assistance to provinces, territories, and NGOs for the provision of family justice services. This broad focus allows for continued alignment over time with the needs in the family justice sector.

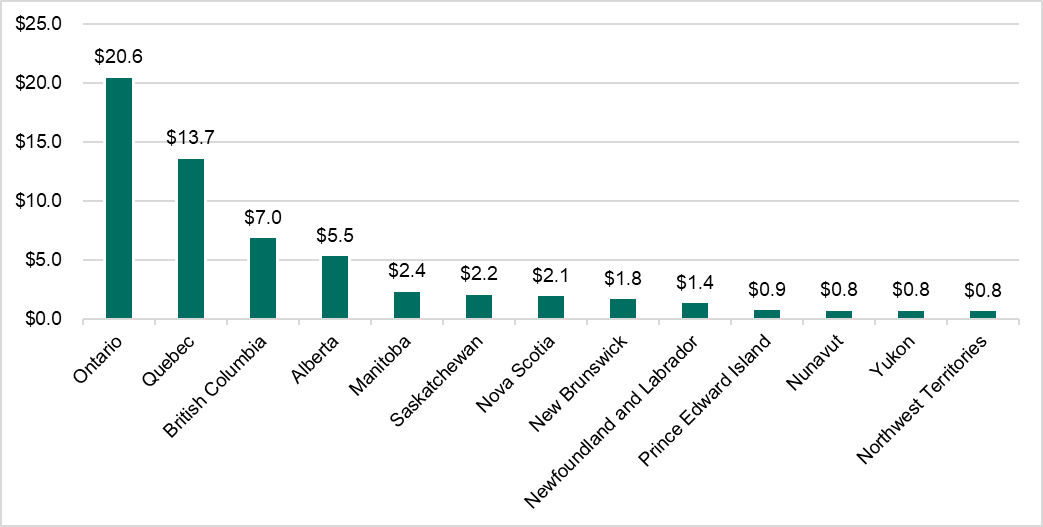

CFJF supported PTs activities

The CFJF has responded to the needs by committing approximately $60.0M in funding to PT governments to implement CFJF-related activities, between 2018-19 and 2021-22. As indicated in Figure 2, the largest portion of PT activity funding was allocated to Ontario ($20.6M or 34%), followed by Quebec ($13.7M or 23%), and British Columbia ($7.0M or 12%). The amount of funding available for each PT is established using a base and a per capita model with a total of $15M in annual funding for all PTs. The evidence suggests that the CFJF helped maintain extended family justice services and staff in PTs, such as Parent Education Programs, Supervised Access and Visitation Programs, Mediation Services, Maintenance Enforcement, and Child Support Recalculation services.

Text version

The above Figure 2 represents CFJF activity funding by PT agreement, in $ million, between 2018-19 and 2021-22.

The amount, by PT, is as follows:

- Ontario: $20.6

- Quebec: $13.7

- British Columbia: $7.0

- Alberta: $5.5

- Saskatchewan: $2.2

- Nova Scotia: $2.1

- New Brunswick: $1.8

- Newfoundland and Labrador: $1.4

- Prince Edward Island: $0.9

- Nunavut: $0.8

- Yukon: $0.8

- Northwest Territories: $0.8

CFJF supported PTs’ and NGOs’ projects

The CFJF approved $24.2MFootnote22 for 61 CFJF projects from 2017-18 to 2021-22, with some projects starting as early as 2017-18 and some ending as late as 2024-25 (Figure 3). Projects were led by NGOs and other types of organizations, including PT governments. Among projects funded, the largest proportion of project funding was allocated to projects in British Columbia (37%) followed by Ontario (25%). As part of the evaluation analysis, the CFJF projects were coded according to the five priority areas as well as whether they focused on Divorce Act changes implementation. The largest proportion of CFJF project funding focused on improving and streamlining family justice system links (62%), followed by meeting the needs of diverse and underserved communities (27%), and implementing Divorce Act changes, for example, through the update and development of new PLEI materials (26%).

Text version

The above Figure 3 represents CFJF project funding approved by PT, in $ million and number of projects, between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

The amounts, by PT, are as follows:

- British Columbia: $9.0, 7 projects

- Ontario: $6.1, 10 projects

- Nova Scotia: $1.6, 6 projects

- Manitoba: $1.5, 3 projects

- Newfoundland and Labrador: $1.5, 4 projects

- Prince Edward Island: $1.4, 5 projects

- Saskatchewan: $1.1, 7 projects

- Yukon: $0.7, 3 projects

- New Brunswick: $0.4, 5 projects

- Alberta: $0.4, 6 projects

- Quebec: $0.3, 3 projects

- National: $0.1, 1 project

- Northwest Territories: $0.03, 1 project

There is a low likelihood that activities and projects would have proceeded without funding from the CFJF

The evaluation found that there is a low likelihood that activities/projects would have proceeded as planned in the absence of the CFJF. Without the funding, some activities/projects may have continued but at a smaller scope and with a longer time frame. The funding is essential in ensuring new services are piloted and tested.

On average, PT and NGO representatives interviewed indicated there is a low likelihoodFootnote23 that the activities/projects would have proceeded as planned in the absence of the CFJF. Without the funding, some activities/projects may have continued but with a smaller scope, with a longer time frame and would be of a lesser quality. The funding is seen as essential in ensuring new and innovative services are piloted and tested, such as piloting the delivery of mediation services in new jurisdictions. Among PTs, though several jurisdictions indicated that the family justice activities are a priority and would still receive funding even without the CFJF, others indicated that the extent, efficiency, and quality of the services would be impacted if the funding was lost. Several jurisdictions outlined that the loss of funding from the CFJF would impact their staffing levels, while a few outlined that pilot projects would not have been possible. A few jurisdictions indicated their family justice services would be more significantly reduced without the CFJF, particularly smaller jurisdictions and jurisdictions with more variability in PT priorities.Among NGOs and project leads, a majority indicated that the project would have been reduced in scope and taken more time to complete without the CFJF. Others explained that the effectiveness of the resources would have suffered, as would services provided. A few PLEI organizations indicated that they may have updated a few resources such as the website to reflect changes to the Divorce Act but they would not have created any new materials. The most frequently noted alternative funding sources included PT government funding, law societies and foundations, other federal government funding sources (such as the Justice Partnership and Innovation Program, Access to Justice in Both Official Languages Support Fund), and volunteers or in-kind resources.

4.1.3 Consistency with Government Priorities and Federal Roles and Responsibilities

The CFJF is consistent with federal and PT government priorities, such as improving access to justice, addressing gender-based violence, and improving access for diverse and underserved groups. The Fund is also consistent with federal roles and responsibilities since family law is a shared responsibility between federal and PT governments.

The CFJF is consistent with government priorities

The evaluation found that the CFJF is well aligned with federal government priorities. In particular, the CFJF is well aligned with Justice Canada’s 2020-21 Departmental priority that “Canadians in contact with the justice system have access to appropriate services enabling a fair, timely and accessible justice system.”Footnote24 The Fund also aligns with federal priorities around addressing gender-based violence and intimate partner violence, particularly the Government of Canada’s Gender-Based Violence StrategyFootnote25 and as highlighted in the 2021 Speech from the Throne regarding the “unacceptable rise in violence against women and girls.”Footnote26 Further, the CFJF aligns with the federal goals to reduce poverty through funding the implementation of Divorce ActFootnote27 amendments which support this priority, for example, through recalculation services which help keep child support amounts up to date. In addition, the CFJF supports PTs in meeting Official Language requirements of the Divorce Act amendments that allow individuals to have their proceedings under the Divorce Act conducted in the Official Language of their choice. The CFJF also aligns with federal government priorities around diversity and inclusion, as indicated in the 2021 Speech from the Throne: “fighting systemic racism, sexism, discrimination, misconduct, and abuse, including in our core institutions,”Footnote28 through its support for increased access to family justice for diverse and underserved communities.

Further, the PTs agreed that the CFJF aligned with their PT government priorities. PTs commonly emphasized the CFJF aligns with their overarching objectives, facilitates access to family justice services for families going through separation and divorce, that they have a shared priority on services for diverse and underserved populations, they have a shared focus on supporting the well-being of families and children, and that they have a focus on reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and making programs more accessible to diverse communities, including rural and remote communities.

The CFJF is consistent with federal roles and responsibilities

Family law in Canada is an area of shared responsibility between the federal and provincial and territorial governments, as a result of the distribution of legislative powers under the Constitution Act, 1867. The federal government is responsible for laws regarding marriage, divorce, and federal support enforcement, while provincial and territorial governments are responsible for the administration of justice and for family law matters pertaining to unmarried couples who separate, and married couples who separate but do not divorce. PTs provide the bulk of family justice services. The federal government assists and promotes the development and maintenance of family justice services to facilitate access to the family justice system for families experiencing separation and divorce.

Through the CFJF, Justice Canada fulfils its responsibility by contributing financial assistance to the PTs for the provision of family justice services that support the needs of families experiencing separation and divorce, and by funding non-governmental organizations and individuals for family justice activities.

All Justice Canada and PT representatives agreed that the delivery of the CFJF is an appropriate role for the federal government. In addition, Interviewees indicated the CFJF supports PTs to participate in FPT collaboration, for example, through the Coordinating Committee of Senior Officials - Family Justice (CCSO-FJ), which has allowed for cross-jurisdictional learning.

4.2 Effectiveness

4.2.1 Contribution to Improved Capacity in PTs to Provide Family Justice Services

The CFJF supported improved PT capacity to provide and deliver family justice services, particularly through enhanced funding to ongoing family justice services and funding pilot projects for new services.

The CFJF contributed to an improved capacity for family justice services

The evaluation found that the CFJF improved PTs’ capacity to provide family justice services, which allowed them to maintain services and to pilot new services. Some current PTs’ programs (e.g., child support recalculation services, parenting after separation curriculum, high conflict parenting curriculum, and a family law centre) would not have been piloted and ultimately funded by the PT if not for the CFJF support. The evidence suggests that the CFJF has allowed PTs to deliver more and higher quality services, particularly those targeting diverse and underserved groups. Also, funding had a significant impact on the smaller PTs that have fewer resources compared to larger PTs.

Some specific examples of areas where capacity has been enhanced were identified by the evaluation. The examples are listed by CFJF priority area and as they relate to the implementation of the Divorce Act amendments:

- Fostering Federal, Provincial and Territorial Collaboration. A majority of PTs participated in the research subcommittee as part of the CCSO-FJ. PTs also participated in sharing survey results such as the Justice Canada Exit Surveys, Surveys of Family Courts, Survey of Maintenance Enforcement Programs, and Social Domain Linkage Environment projects. PTs collaborated in service delivery through participation in Inter-jurisdictional Support Order services and working groups.

- Supporting Well-being of Family Members.Footnote29A majority of PTs provided a Maintenance Enforcement Program (available in all 13 PTs) and a Supervised Access and Exchange program (available in 7 PTs). In 2021-22, Nova Scotia reported providing 134 referrals to its Supervised Parenting and Exchange Program with 192 children served. Further, in 2020-21 the Northwest Territories and Prince Edward Island reported a combined 2,599 active Maintenance Enforcement files which resulted in collecting and disbursing over $13.0 million in child support and spousal support. Also, Prince Edward Island has a parenting coordinator position that helps support families experiencing high conflict.

- Reaching Diverse and Underserved Populations. PTs provided services for various diverse and underserved communities. For example, Newfoundland and Labrador provided Parent Education programs and support information material in English, French, Inuktitut, Innu-aimun (Mushuan dialect and Sheshatshiu dialect). Other PTs provided distance mediation services for northern, rural, and remote communities. British Columbia developed an Online Parenting After Separation course for Indigenous Families. Some PTs undertook research such as Quebec, which conducted research on mediation within the Indigenous Population and on 2SLGBTQI+ parents. New Brunswick developed a 20-minute family law information animated video with closed captions to increase the accessibility of the resource.

- Supporting Alternatives to Court. Most PTs provided out-of-court dispute resolution and mediation services (available in 11 PTs) (including bilingual mediation and distance mediation) conflict-specific interventions (available in 3 PTs), as well as other dispute resolution programs such as the dispute resolution officers program (Ontario), collaborative law (Saskatchewan), conciliation services (Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island), parenting coordinators (Prince Edward Island), and family court counsellors (Alberta). For example, according to annual reports in 2020-21 and 2021-22, seven (7) PTs provided mediation services to 22,453 clients annually, at an average of 3,208 clients per PT.Footnote30 In 2020-21, Alberta reported addressing 1,343 applications in 4 Caseflow Conference locations in Provincial Court and 1 in the Court of Queen’s Bench location. Similar to mediation, Caseflow Conferences offer an alternative to court for resolving family law issues and it is estimated that Alberta’s Caseflow Conference activities saved 524 days of court time. Most PTs provided Child Support Recalculation services (available in 8 PTs). For example, according to annual reports in 2020-21 and 2021-22, four (4) PTs delivered a total of 5,856 recalculation services annually, at an average of 1,464 services per PT.Footnote31

- Improving and Streamlining Family Justice System Links/Processes. As noted earlier, several PTs provided Child Support Recalculation (9 PTs)Footnote32 and Inter-jurisdictional Support Order services as well as Maintenance and Enforcement Programs (13 PTs). A few PTs noted other services such as triage and intake services, services for self-represented litigants (e.g., a 12-week course), and court ordered evaluation support programs.

- Research Requirement. Most PTs participated in surveys such as the Family Justice Services Exit Survey, Social Domain Linkage Environment project, Parent Education Programs Survey, Survey of Family Courts, Maintenance Enforcement Projects Survey, and Family Mediation Services Survey. Several also noted that they collect data on access to information and services (e.g., PLEI materials, out-of-court dispute resolution options, referrals to mediation, training of staff, etc.). Several referred to participation in the CCSO-FJ Research Subcommittee and a few noted internal evaluation and research projects (e.g., dispute resolution, mediation, and maintenance enforcement programs).

- Improved capacity related to Divorce Act amendments. PTs have updated PLEI materials to ensure they reflect the amendments. In addition, dispute resolution programs that focus on the best interest of the child were introduced, and services related to supervised parenting time were developed, and funding was accessed to implement the Official Languages provision in the Divorce Act.

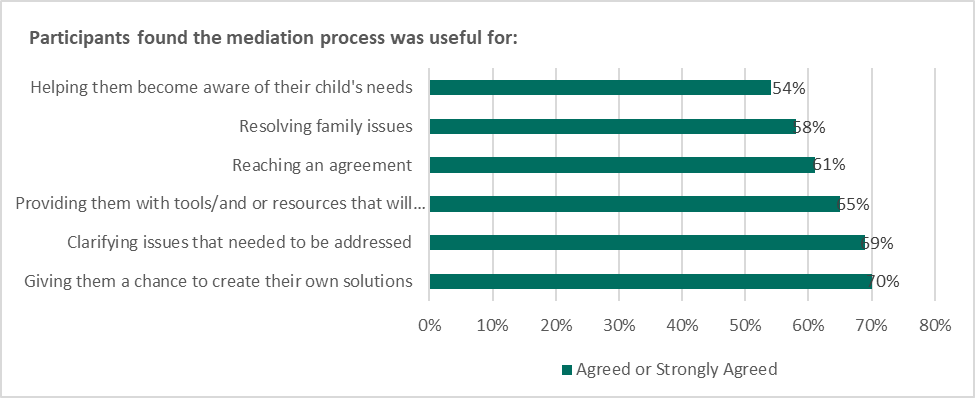

Results from the Mediation Services Program Survey indicate that mediation services offered were useful

The Mediation Services Program Survey provides information on participant perceptions of the usefulness of the mediation services in helping them to resolve disputes and avoid court. Survey resultsFootnote33 indicate that, where the services were available, participants found the services useful in clarifying issues that needed to be resolved, providing them with tools, and helping them to create their own solutions to resolve family law issues outside of court.

Text version

The above Figure 4 represents the reasons participants found the mediation process useful between 2017-18 and 2020-21.

By percentage, participants found the mediation process was useful for:

- Giving them a chance to create their own solutions: 70% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Clarifying issues that needed to be addressed: 69% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Providing them with tools/and or resources that will have utility in the future: 65% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Reaching an agreement: 61% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Resolving family issues: 58% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Helping them become aware of their child's needs: 54% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

Contribution to Increased Awareness, Knowledge, and Understanding of Family Law and Children’s Law Issues Among Targeted Audiences

The CFJF supported an increase in awareness, knowledge, and understanding of family law and children’s law issues among targeted audiences through the development, update, and delivery of PLEI materials, particularly in response to Divorce Act amendments, the delivery of one-on-one engagements (i.e., by email and telephone), and the delivery of parent education programs.

The CFJF contributed to raising awareness, knowledge, and understanding of family law and children’s law issues

A variety of PLEI materials, courses and programming have been supported through the CFJF. PTs often mentioned family law information sessions and workshops, family law centres, and parenting after separation courses. PTs also referred to printed materials and websites which have been updated and expanded due to the CFJF. NGOs and Justice Canada representatives similarly noted that considerable new PLEI resources and publications have been developed with the support of the CFJF. Publications have been promoted to diverse organizations and populations such as mental health professionals, Official Language Minority Communities, Indigenous peoples, newcomers, people living in rural and remote areas, and legal professionals. Much of the updates have focused on the Divorce Act amendments. Examples of activities undertaken by PTs and NGOs to increase awareness, knowledge, and understanding of family law and children’s law issues are as follows:

- Update, development, and distribution of PLEI materials: PTs and NGOs updated, developed, and distributed information about family justice issues. For example, Nunavut developed a video on the perspectives of children and a children’s activity book, which was translated into four languages. The materials were distributed to 23 communities including key stakeholders (e.g., Royal Canadian Mounted Police). Similarly, Saskatchewan reported developing six short videos on family law topics. In 2021-22, Saskatchewan reported distributing 3,075 family justice PLEI kits by mail or email, covering topics such as divorce, agreement, Inter-jurisdictional Support Orders, pleadings, Chambers motions, and pre-trial information and delivering 16 virtual help sessions with a total of 43 attendees. In 2020-21, the Northwest Territories reported that the “Family Law in the Northwest Territories” publication was available online and through printed copies (400 copies were printed in English and 50 copies were printed in French).

New PLEI materials were developed by NGOs, such as an Agreement Maker platform tool for self-represented litigants on the Family Law Saskatchewan website.Footnote34 The tool takes families through a series of questions about what they are seeking, in the way of an agreement which could include separation, support agreements, parenting agreements, etc. At the end, an agreement document is generated and intended to serve as a first step in a separation or divorce. Uptake of the tool more than doubled between 2018 and 2022, from 3,000 to 7,000 users. Another project expanded an existing pan-Canadian PLEI website to include the three territories. The Families Change WebsiteFootnote35includes age-appropriate content for children, teenagers, and adults to help them learn how to deal with a family break up. The website includes games and interactive elements for children. Other projects developed guidelines for families to access online such as “tips for talking with an ex during a separation” created by the People’s Law School in British Columbia.Footnote36 - New training, workshops, and services: One project funded by the CFJF developed a 12-week practical course for self-represented litigants including weekly 1.5-hour live classroom sessions covering foundations, paperwork and forms, legal research, settlement procedures and options (e.g., mediation), hearings, preparing for trial and conducting a trial, and self-care. The course includes guest speakers such as judges, lawyers, and other self-represented litigants. There was a high demand for the course as it filled up in 2 hours with 40 participants after registration opened. Another project developed a workshop for parents preparing for supervised visitations to help them with healthy relationship foundations, co-parenting, and how to manage emotions and be more flexible in high-conflict situations. A total of 75 individuals had participated in the workshop as of June 2022.

- Parent Education Programs:All 13 PTs delivered parent education programs. For example, according to annual reports in 2020-21 and 2021-22, eight (8) PTs provided parent education programs to 12,886 clients annually, at an average of 1,611 clients per PT.Footnote37 Some programs were delivered in a correctional centre (Yukon), some focused on managing conflict (Saskatchewan), some were offered in French for the first time (Alberta), and some targeted youth counsellors in schools (Northwest Territories).

- Client Engagements (e.g., phone calls, emails, website views, etc.): PTs reported increasing awareness through telephone, email, and in-person engagements. For example, according to annual reports in 2020-21 and 2021-22, six (6) PTs provided 23,981 client engagements annually, at an average of 3,997 client engagements per PT.Footnote38 Topics included divorce, child support, child custody, parental access rights, parent education, family violence, maintenance enforcement, as well as support for self-represented litigants.

- Website Page views/User Data: PTs shared information about family justice issues through their websites. For example, in 2021-22, Saskatchewan reported there were 15,902 external page views and 12,690 external unique page views of their family justice services website. In the same year, Nova Scotia reported there were 89,139 total website downloads, 54,377 total external resources visited, and 1,663 total phone numbers and email clicks. In 2020-21, Manitoba reported that its Family Law website was accessed by over 40,000 users, approximately 2,000 people visited the For the Sake of the Children page, and approximately 1,300 people visited the Family Law Parenting Program for the Sake of the Children eCourse.

The case studies provided further evidence that the CFJF has contributed to increased awareness (Figure 5).

| Organization: Luke’s Place Support and Resource Center for Women and Children (Ontario) |

|---|

| Project: Building Awareness about Divorce Act Changes Impacting Women |

| Funding: $141,775 in funding from the CFJF (2021-22 to 2022-23) |

|

Objectives, Activities and Impacts: The primary objectives of the project were to increase survivors’ (women who have been in abusive relationships) understanding about changes to the Divorce Act as it relates to family violence and parenting relationships, and to help advocates (usually community-based service providers in women’s shelters, and other organizations) who support survivors to understand what those changes are by equipping advocates with the most up-to-date legal information and strategies. The project developed a toolkit of legal and safety information for women leaving abuse and an “After She Leaves” family law training for women’s advocates and updated the “After She Leaves” manual and “Family Court and Beyond” website. Between December and March 2022, there were over 600 downloads of the toolkit. Between December 2021 and March 2022, there were 117 family law advocates enrolled in “After She Leaves” family law training for family law advocates and 93% of participants indicated they will recommend the course to others. Highlights from 25 e-learning evaluations completed by individual workers between April 30 and June 2, 2022, are as follows: 56% reported a very high level of learning; 76% reported increased confidence in providing family court support; 84% would recommend the course to others doing the work; 88% found the course easy to navigate; and 52% identified as being located in northern Ontario. |

| Organization: Le Petit Pont (Quebec) |

| Project: Let's equip parents for the future of children and our community |

| Funding: $246,467 in funding from the CFJF (2017-18 to 2020-21) |

|

Objectives, Activities and Impacts: The objective of the project was to assist in carrying out and evaluating parental, family or conflict coaching meetings with parents and children, allowing coaches to observe and analyze the difficulties that arise in the context of separation or divorce, and to propose concrete advice and provide follow-up. Parental coaching focused on the well-being of the family to develop ways that can prevent conflict rather than trying to heal families in the aftermath of conflict. The parental coaching model provided by Le Petit Pont has been adapted to facilitate parent-child bonds during a separation or divorce. The coach helps family members better understand the source of the problems and set realistic goals. Then, using targeted intervention strategies, tips, and practical exercises, the coach helps parents and children achieve a more harmonious family dynamic. The project served 49 families and delivered 203 coaching sessions. The project found that in 77% of cases, parents improved their awareness and understanding of strategies to minimize conflict and improve family wellbeing. |

Results from the Parent Education Program Survey indicate that courses delivered increased awareness and knowledge

The Parent Education Program Survey provides information on participant perceptions of how their awareness and understanding of the family justice system and other related topics increased as a result of their participation in parenting courses (e.g., Parenting After Separation). Survey resultsFootnote39 indicate that the courses contributed to increased understanding and capabilities among parents experiencing separation or divorce, particularly with respect to their understanding of the impact of separation and/or divorce on children and their ability to talk to children about these issues.

Text version

The above Figure 6 represents participants’ improved understanding after participating in the mediation process between 2017-18 and 2020-21.

By percentage, after participating in the mediation program, participants gained a better understanding of:

- The impact of separation and/or divorce on children: 90% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Alternatives to court (e.g., mediation, collaborative family law): 87% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Parents responsibilities (e.g., financial support for children, parenting time, etc.): 85% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- The impact of separation and/or divorce on parents: 84% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Child support guidelines: 79% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

Text version

The above Figure 7 represents participants’ improved capabilities after participating in the mediation process between 2017-18 and 2020-21.

By percentage, after participating in the mediation program, participants felt they were better able to:

- Understand their children's needs: 89% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Talk to their children about separation and divorce: 87% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Make family changes easier for children: 87% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Approach issues or concerns with respect to their family situation: 82% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

- Address conflict with respect to family law issues: 80% Agreed or Strongly Agreed

Contribution to Increased Access to Family Justice for All Canadians

The CFJF contributed to increased access to family justice for Canadians, particularly through mediation and recalculation services, as well as through PLEI resources and courses that have been developed to help families navigate the system.

The evaluation found that the CFJF has contributed to increased access to family justice for Canadians. The most commonly identified ways the Fund has contributed include:

- Family mediation. It was noted that the service has particularly increased in Quebec and the Northwest Territories, and that the service is new to Yukon as a direct result of the CFJF. For example, in 2021-22, Quebec reported that there were 1,202 accredited mediators in the province and 15,435 couples benefited from mediation under the program. In 2020-21, the Northwest Territories reported that 31 mediation files opened, an increase from the 25 files opened in 2019-2021.

- Recalculation services. As noted earlier, most PTs provided Child Support Recalculation services (available in 9 PTs).Footnote40For example, according to annual reports in 2020-21 and 2021-22, four PTs delivered a total of 5,856 recalculation services annually, at an average of 1,464 services per PT.

- PLEI materials.These resources have helped families navigate and access the justice system, particularly resources for self-represented litigants and there has been a significant demand and uptake for these resources (e.g., the 12-week course funded through CFJF was full within 2 hours of opening registration).

The case studies similarly identified examples of ways that the CFJF has increased access to family justice services. In the Luke’s Place case study project, the funding supported the design of new products to support access to family justice services: a toolkit on parenting after separation and new laws for women; an “After She Leaves” family law course for advocates; updates on the “After She Leaves” manual for service providers; and updates for a “Family Court and Beyond” resource package which comprises the website, workbook, and organizer. While there are no direct means to measure the impact of these products on improving family justice service, it can be inferred from the frequent downloads and feedback from service providers that the program was beneficial in that regard. The Le Petit Pont case study also developed a new coaching service for high conflict families experiencing separation and/or divorce, that otherwise would not have existed without the CFJF.

4.2.4 Contribution to Improved Access to Family Justice Services for Vulnerable Populations

The CFJF contributed to improved family justice services for diverse and underserved populations through innovative projects and activities which target Indigenous peoples, northern, rural, and remote populations, Official Language Minority Communities, newcomers, and 2SLGBTQI+ individuals. The CFJF is generally flexible in addressing the needs of diverse groups.

In April 2022, six PTs indicated that they measured the reach of programs and services to diverse and underserved populations with an exit questionnaire or review. One jurisdiction noted they used Google Analytics to collect statistics about how many people are accessing their online services and what they are searching for. Three PTs indicated they did not collect any data specific to diverse and underserved populations. Some examples of ways in which activities and projects contributed to improved family justice services for diverse and underserved populations are as follows:

- Indigenous peoples. Nova Scotia developed public legal information on Family Homes on Reserve and Emergency Protection Order legislation and related First Nation laws. This information has been made available in Mi’kmaq and English and narrated in Mi’kmaq on the Nova Scotia family law website. British Columbia and Ontario have developed parent education programs for Indigenous families. Yukon and Nunavut have taken steps to ensure that mediation services are culturally appropriate for their residents. Nunavut’s family mediation service combines southern-based mediation techniques with traditional Inuit approaches to problem-solving to deliver culturally relevant dispute resolution services to Nunavummiut people. As noted earlier, Newfoundland and Labrador provided parent education program and support information material in English, French, Inuktitut, Innu-aimun (Mushuan dialect and Sheshatshiu dialect). Some PTs have recorded information in Indigenous languages so the content can be listened to by those with literacy barriers.

- Northern, rural, and remote populations. In the Northwest Territories, family justice services are available in remote communities where family law lawyers are not commonly located. Without these services, these communities would not have access to family justice services or would need to find alternative ways to access services. In Nunavut, mediation services and resources have been made accessible in 23 of 25 communities served. Newfoundland and Labrador provided services in northern, rural, and remote communities and distributed PLEI materials in the different languages of those communities.

- Official Language Minority Communities. Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Nova Scotia translated their Parenting After Separation courses into French. Nova Scotia translated its family law website into French and developed a French-English Family Justice Lexicon consisting of 960 family law terms along with information about where each family law term may be found in different Acts, Rules, Regulations or Guidelines. British Columbia made French-language interpreters available when necessary and translated several publications into French.

- Newcomers. One NGO created a family law publication for recent immigrants. In some urban centers in Ontario, mediation service providers have ensured their roster of mediators reflects the community they are serving. Yukon has also developed a culturally diverse roster of mediators with different linguistic proficiencies.

- 2SLGBTQI+ individuals. In 2020-21, Ontario led FPT research regarding how to improve access to family justice services for the 2SLGBTQI+ community. In 2021-22, Quebec undertook research on the judicial journey of separated or divorced parents of 2SLGBTQI+ individuals and research related to legal professionals and intermediary interactions with 2SLGBTQI+ parents.

It was noted that there has been more of a focus on projects and activities that target diverse and underserved groups in the recent calls for proposals. Legislative amendments in the Divorce Act also include requirements for courts to consider the child’s culture and heritage in determining the best interests of the child when making a parenting or contact order. Also, if a province or territory has implemented the language rights provision and a family justice service is a mandatory step in a proceeding under the Divorce Act, those services must be available in either official language.

A majority of interviewees perceived that the CFJF is very flexible in meeting the needs of diverse and underserved population groups. For example, the priority categories are broad, the implementation of agreements is flexible to accommodate project changes and delays, and the annual reporting includes specific questions about whether the project is reaching diverse and underserved populations. A few interviewees noted that the 5-year PT contribution agreements and low amount and time-limited funding dedicated to projects ($1M annually for projects Canada-wide) limits flexibility to some extent.

The case studies provided further evidence that the CFJF has supported increased access to family justice services for diverse and underserved populations (Figure 8).

| Organization: British Columbia Ministry of Attorney General, Family Justice Services Division. |

|---|

| Project: Online Parenting After Separation for Indigenous Families |

| Funding: $103,000 in funding from the CFJF (2017-18 to 2019-20) |

|

Objectives, Activities and Impacts: The objective of the project was to develop, implement and evaluate a culturally sensitive and appropriate online version of the Parenting After Separation program for Indigenous parents in British Columbia. The project established an advisory committee with representation from different Indigenous organizations across the province and included on-reserve, urban, rural, First Nations and Métis individuals. Only Indigenous peoples were featured throughout the course curriculum in videos and photos and Indigenous peoples were hired to develop different aspects of the course content (e.g., graphic design, narration, etc.). There was a thorough feedback, validation, and consent process with the advisory committee and individuals featured in the course. Online Parenting After Separation for Indigenous Families participant survey results showed that, on average, 86% of participants who completed the course from November 26, 2019 to March 31, 2021 agreed or strongly agreed that because the course was culturally appropriate, they were more engaged with the course in a more meaningful way. The course resulted in the following impacts:

|

4.2.5 Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Effectiveness

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a shift to offering more services virtually that were previously in-person, while the delivery of PLEI resources was largely unaffected. The shift online had both positive and negative impacts on effectiveness.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many family justice services moved from an in-person to a virtual delivery model. For example, mediation and parenting after separation courses were offered online. The move also accelerated the acceptance of offering services online by different stakeholder groups. The use of technology and the shift to virtual delivery became essential during the pandemic and in some jurisdictions was the only safe and permitted option for Canadians to access the family justice system.

Advantages of virtual services: The shift to a virtual service delivery model had several advantages. Virtual services allowed for increased access and uptake. Virtual delivery allowed for flexible scheduling and eliminated the need for travel and childcare. One jurisdiction saw an increase in uptake of the online high conflict parenting after separation course but not the general parenting after separation course. Some jurisdictions used online services to increase their reach to more rural and remote areas and develop online resources tailored to specific diverse and underserved groups. In some family violence cases, virtual delivery provided increased safety since the parties did not need to be in the same room. Virtual delivery also increased the comfort of many individuals in accessing family justice services. Justice Canada’s 2021 National Survey found a relatively high comfort rating in their sample of 3,200 Canadians: 87% of respondents indicated that they were moderately or highly comfortable with looking for information and reading about the family justice system online; 80% with completing forms online using fillable PDF forms; and 71% with using videoconferencing platforms for meetings, mediation, and court sessions. Further, providing services online instead of in-person reduced administrative costs of family justice services, particularly parent education programs.

Disadvantages of virtual services: There were some disadvantages to the shift to virtual service delivery. There was still an overall reduction in family justice services, particularly during the transition to virtual delivery. There were delays in accessing services which created backlogs in accessing family lawyers and legal aid services. Staff turnover and burnout particularly among NGOs serving survivors of family violence further strained access to services. New access barriers were created with virtual delivery, particularly for those with limited internet connectivity and access to technology. It was more challenging to deliver effective services to some groups such as newcomers, family violence survivors, older adults, persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, and people living in rural and remote communities. In addition, not all virtual services and materials were available in an accessible format, i.e., adjustable font sizes, vocabulary used, and navigability.

4.3 Efficiency

4.3.1 Management of the CFJF

Overall, the CFJF is managed efficiently due to good working relationships between funding recipients and CFJF staff, reasonable reporting, and multi-year funding. Some constraints were identified regarding communication, the availability and consistency of performance data, and the limited program budget.

Generally, the evidence suggests that PTs and NGOs had an effective working relationship with CFJF staff. The reporting was seen by PTs and NGOs as reasonable with many indicating it was an improvement over the previous funding cycle, due to the improved table template with planned activities in one column and the corresponding actual results in another column, and the elimination of the interim report requirement. The multi-year funding structure was also appreciated to reduce the administrative burden related to planning and reporting. Further, the CFJF was flexible about contribution agreement timelines and moving funding between line itemsFootnote41 to adapt to unexpected changes in project implementation particularly arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other factors contributed to the efficient management of the Fund. For example, the criteria included as part of the review process and the template for completing the review reports, the streamlined payment process, and the good communication with recipients and the coordination with other funds. It was also noted that Justice Canada liaises with PTs who work with NGOs within their region to identify key priority areas. This is done to avoid redundancies in what is funded.

Some constraints were identified with respect to the efficient management of the CFJF. There were gaps in communication between Justice Canada and PTs and NGOs. For example, there was a lack of awareness that the list of approved projects and funding amounts is published through quarterly proactive disclosure of grants and contributions. It was also noted that there is a need to more proactively engage PTs and NGOs to clarify priorities in calls for applications and address questions such as what constitutes a “diverse and underserved group.”

As noted earlier, there were gaps associated with the CFJF program performance data. For example, not every jurisdiction participates in Justice Canada’s family justice surveys and there is an overrepresentation of some PTs relative to others depending on the survey, which can skew the results. For example, 75% of survey participants in the Parent Education Program survey were from Alberta, while 8 PTs participated. However, an effort is currently underway, in collaboration with PTs to update and improve these surveys; revised versions of the surveys will be implemented in 2022-23.

Further, the timing and format in which final reports are received from PTs and NGOs varies making it difficult to aggregate data across reports. The data is not captured in a standardized manner to facilitate monitoring and reporting on outcomes. In addition, several reports were received late from the PTs. At the time of the evaluation reporting stage, in October 2022, final reports for the 5-year funding agreements for 6 out of 13 PTs had not yet been received by Justice Canada which were due in June 2022.

The evaluation also identified some evidence that the budget for the CFJF is limiting its effectiveness. Evidence suggests that the CFJF budget limits the impact the Fund can have, and the fund has not had an increase since 2002-03Footnote42 which means, in real dollars, the amount of funding has decreased over the years when inflation is considered. This situation created challenges for some jurisdictions to address identified gaps in services.

4.3.2 Extent Best Practices and Lessons Learned are Identified, Communicated, and Applied in the Delivery of the CFJF

Best practices and lessons learned were identified as part of the evaluation. For CFJF activities/projects, these included engaging diverse and underserved stakeholders when developing services for these groups, ensuring sufficient time for meaningful engagement and collaboration, implementing strategies to mitigate negative impacts of virtual service delivery, and ensuring services are accessible in both Official Languages (among others). For Justice Canada’s management of the CFJF, best practices consisted of maintaining flexibility in working with funding recipients and keeping reporting simple. Best practices are well-communicated and shared across FPT stakeholders.

Best practices and lessons learned were identified as part of the evaluation. Best practices are well-communicated and shared across FPT stakeholders. The following examples of best practices and lessons learned were identified through key informant interviews, case studies and the document and data review:

Best practices were identified for CFJF activities/projects

- Engage stakeholders from the target group community in developing courses and materials. Stakeholders should be engaged in the co-development and co-design of services and materials. For example, as part of the Online Parenting After Separation for Indigenous Families course, an advisory committee was struck to guide the course development process. The advisory committee included representation from different Indigenous organizations across the province including on-reserve, urban, rural, First Nations and Métis individuals. The advisory committee worked to ensure that the diversity of Indigenous peoples was recognized throughout the course and contributed to the course being culturally relevant and appropriate. Additionally, the advisory committee contributed to the promotion of the Online Parenting After Separation for Indigenous Families course by referring and recommending Indigenous families to it. This approach is closer to the “with us, by us” approach of developing courses and materials aimed at Indigenous peoples, rather than the “about us, for us” approach which does not include this level of engagement and co-development. Only people from these communities can understand the nuances required from their own lived experience and infuse this in the products developed.

- Ensure sufficient time for meaningful engagement and collaboration with target groups in the design of course products and materials. Meaningful engagement and collaboration takes time and requires a multi-step process of co-development, validation, and consent. There is a need for flexibility in the timelines of funding deliverables since working with groups in a meaningful way takes time and requires flexibility.

- Implement strategies to mitigate negative impacts of virtual service delivery. Some strategies identified include offering multiple service delivery options including maintaining in-person services for those who need them, focusing on user-centred design of virtual services and tools, leveraging existing virtual services (e.g., parenting after separation courses offered by other PTs), considering PT collaboration or sharing of virtual services to reduce costs, developing protocols to ensure survivors of family violence are safe to participate in a virtual environment, and training staff on identifying and mitigating risks in virtual service delivery.

- Ensure services are made available in both Official Languages and provide interpreters for other languages. For national projects, it is better to let each region handle English and French translation since each region has its own terminology. Make services available in both Official Languages and have interpreters for other languages (including Indigenous languages).

Best practices were identified for the management of the CFJF

- Continue to maintain flexibility and offer solutions in working with funding recipients. Some projects found that the approach of the CFJF staff of being effective collaborators in the project contributed to ensuring the project was a success. For another project, the support, collaboration, and follow-up of Justice Canada was seen as important and appreciated. The support made it possible to identify solutions and adjust as the project progressed, as the external environment may cause additional difficulties (e.g., labour shortages, pandemic, etc.).

- Continue to offer a simple and easy-to-follow reporting template. It was found that the CFJF reporting template is seen as very simple, straightforward, and easy to navigate. One organization was able to complete the report in less than a day. The simplicity of the reporting tool made the process very efficient such that more time could be channeled into the delivery of the program.

All the jurisdictions share valuable information as members of CCSO-FJ and through its working groups. Further, almost all jurisdictions (n=10) engage in collaboration with another province or territory, which included the sharing of programs, services, or adapted practices. With increased provision of online services, there has been an increase in collaboration through the sharing of online resources and training guides. Additionally, the CCSO-FJ formulates and shares recommendations, such as recommendations on the use of technology to inform FPT planning and priority setting. Justice Canada representatives indicated that best practices and lessons learned are communicated within Justice Canada and to/from funding recipients primarily through project reporting. NGOs and PTs are asked for feedback on administration and lessons learned in their project and Justice Canada analysts share those lessons within Justice Canada and with PTs and NGOs.

- Date modified: